Summary of Futurism

Focusing on progress and modernity, the Futurists sought to sweep away traditional artistic notions and replace them with an energetic celebration of the machine age. Focus was placed on creating a unique and dynamic vision of the future and artists incorporated portrayals of urban landscapes as well as new technologies such as trains, cars, and airplanes into their depictions. Speed, violence, and the working classes were all glorified by the group as ways to advance change and their work covered a wide variety of artforms, including architecture, sculpture, literature, theatre, music, and even food.

Futurism was invented, and predominantly based, in Italy, led by the charismatic poet Marinetti. The group was at its most influential and active between 1909 and 1914 but was re-started by Marinetti after the end of the First World War. This revival attracted new artists and became known as second generation Futurism. Although most prominent in Italy, Futurist ideas were utilized by artists in Britain (informing Vorticism), the US and Japan and Futurist works were displayed all over Europe. Russian Futurism is usually considered a separate movement, although some Russian Futurists did engage with the earlier Italian movement. Futurism anticipated the aesthetics of Art Deco as well as influencing Dada and German Expressionism.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- A key focus of the Futurists was the depiction of movement, or dynamism. The group developed a number of novel techniques to express speed and motion, including blurring, repetition, and the use of lines of force. This last method was adapted from the work of the Cubists and the inclusion of such lines became a feature of Futurist images.

- The Futurists published a huge number of different manifestos, using them to communicate their aesthetic, political, and social ideals. Although both the Realists and Symbolists had previously produced similar documents, the sheer scale with which the Futurists created and disseminated their manifestos was unprecedented, allowing them to transmit their ideas to a wider audience. To assist them logistically with their distribution, the group made use of some of the new technologies they depicted in their art including advancements in mass media, printing, and transportation.

- Many Italian Futurists supported Fascism and parallels can be drawn between the two movements. Like the Fascists, the Futurists were strongly patriotic, excited by violence and opposed to parliamentary democracy. When Mussolini took power in 1922 it brought Futurism official acceptance, but, later, this adversely affected many of the artists as they became tainted by association.

Overview of Futurism

An automobile accident had a transforming effect on Marinetti, who famously said, "a roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace," as the then unknown writer launched Italy’s most important modern art movement.

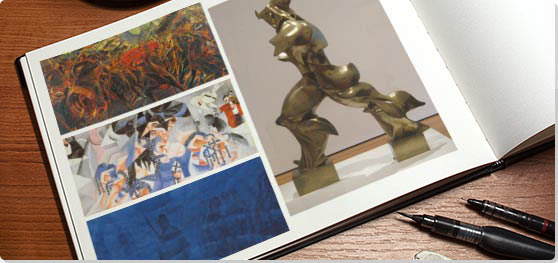

Artworks and Artists of Futurism

The City Rises

This pioneering work launched Futurism when it was exhibited in Milan in the 1911 Mostra d'arte libera (Exhibition of free art). The painting combined the brushstrokes and blurred forms of Post-Impressionism with Cubism's fractured representations.

Originally entitled Il lavoro (Work), it depicts the construction of Milan's new electrical power plant. In the center of the frame, a large red horse surges forward, as three men, their muscles straining, try to guide and control it. In the background other horses and workers can be seen. The blurred central figures of the men and horse, depicted in vibrant primary colors, become the focal point of the frenzied movement that surrounds them, suggesting change is born from chaos and that everyone, including the viewer, is caught up in the transformation. As art critic Michael Brenson notes "Horses and people are forces of nature pitted against and aligned with one another in a primal struggle from which Boccioni must have believed something revolutionary would be born".

The work is a celebration of progress and of the working men that drove it, consequently the workers are depicted on a large scale (the canvas measures 6 ½ x 10 foot) and in a style which references Renaissance ideas of the heroic nude. Boccioni visually conveys modern labor as a glorious battle with the past to create a new future.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Funeral of the Anarchist Galli

This painting commemorates the funeral of Galli, an anarchist killed during strike action. Hundreds, including women and children, attended his funeral procession, which was led by a cohort of anarchists. The painting captures the moment that police mounted on horseback attacked the procession. Carrà was at the funeral and in his later autobiography wrote, "I found myself unwillingly in the centre of it, before me I saw the coffin, covered in red carnations, sway dangerously on the shoulders of the pallbearers; I saw horses go mad, sticks and lances clash, it seemed to me that the corpse could have fallen to the ground at any moment and the horses would have trampled it. Deeply struck, as soon as I got home I did a drawing of what I had seen".

Galli's coffin, draped in a red cloth, is shown in the center of the canvas, held aloft by anarchists, depicted in black. They press energetically forward towards a wall of police cavalry on the left. Rays of light emanate from the coffin, illuminating the dark, merging mass of humanity and indicating Galli as the focus of the piece; referencing his role in igniting the current violence. The top third of the painting is dominated by strong diagonal lines with flagpoles, banners, lances, and cranes suggesting the melee and siege apparatus of war.

Carrà's initial sketches for the work used a more traditional perspective, but, after a trip to Paris with other Futurists in 1910 where they encountered Pablo Picasso's Cubist works, the artist dramatically changed the painting to include fracturing, using it to demonstrate intense movement. This technique was described in a 1912 version of the Futurist Manifesto using Funeral of the Anarchist Galli as a reference. The manifesto noted that "If we paint the phases of a riot, the crowd bustling with uplifted fists and the noisy onslaught of the cavalry are translated upon the canvas in sheaves of lines corresponding to the conflicting forces, following the general law of violence of the picture. These force-lines must encircle and involve the spectator so that he will in a manner be forced to struggle himself with the persons in the picture."

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash

This humorous painting shows a woman, as she walks her small black Dachshund down a city sidewalk. Cropped to an extreme close-up, the woman's feet, along with the bottom folds of her black dress, as well as the dog's feet, tail and floppy ears are multiplied and depicted in varying degrees of transparency and opacity. The fine metal leash becomes four parabolic curves connecting the woman to the dog. This repetition and replication of the moving elements creates a sense of forward motion which is in opposition to the pavement's diagonal lines.

In creating this image, Balla drew upon chronophotography. In 1882 Etienne-Jules Marey invented the chronophotographic gun, which allowed successive movements to be depicted in one photograph. This is one of a number of ways that the Futurists tried to capture movement on canvas and a similar technique can be seen in some of Balla's other works such as Girl Running on Balcony (1912). Yet, as art curator Tom Lobbock writes, the painting "Even without these multiplication and motion effects... would be doing something that's novel. There aren't many previous paintings that present us with such an abrupt close-up. Balla takes the kind of subject that Impressionism had specialised in...but he picks out only a single detail, an almost randomly chosen clip, and makes it the focus of the whole picture...a trivial subject is made into the main event".

Oil on canvas - Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York

Dancer at Pigalle

The dancer, depicted in the middle of the painting is composed of a dynamic intersection of lines and swirling fabric. Four beams of stage lighting focus inwards on her, highlighting her as the center of the image whilst, in contrast, her rapid, rotational movements radiate out in concentric circles to the edges of the pictorial plane. Each of these circular layers contains fragmentary images of musicians, instruments, viewers, and shapes evoking musical notes, capturing an essence of the space in which she performs.

Italian born and raised, Severini moved to Paris in 1906 where, living in the Montmartre district, he became friends with Georges Braque, Juan Gris, and Pablo Picasso, whilst also maintaining connections with the Futurists. It was at Severini's instigation, that Boccioni and Carlo Carrà traveled to Paris to view the works of the Cubists. The subject matter of theater and dance was unique to Severini within the context of the Futurist movement, as art historian Maria Heidinger notes, he "set himself apart from standard Futurist ideology that glorified machinery by using dancer and dancehall subject matter to generate a mood and sense of 'collective consciousness' that was equated with modern Parisian social life". Between 1910-14 he painted over a hundred works depicting dancers.

Severini often incorporated 3D elements into his work creating canvases that were a hybrid between painting and sculpture. In this image this takes the form of sequins glued to the painting, which catch and focus light, and the use of gesso to build up the surface of the work in certain areas. In some ways, this technique makes the image more tangible, giving it a sense of shape and texture but it also creates contrasting experiences for the viewer when the canvas is seen from different angles and perspectives.

Oil and sequins on sculpted gesso on artist's canvasboard - Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, Maryland

The Cyclist

Goncharova was a leader of the Russian avant-garde and a key figure in the Moscow Futurists. Here, she depicts a cyclist pedaling past storefronts which display advertisement hoardings. The Russian Futurist fascination with print, text, and typography can be seen in the bold letters on these billboards. Translated, the words read "hat", "silk" and "thread", along with an isolated "Я" which functions as an artist's signature. The choice of these items probably reflects Goncharova's interest in textiles and design and may relate to her proto-feminist emphasis on the equal importance of women's work.

The cyclist's feet, legs, and body, along with the frame and wheels of the bicycle, are multiplied to convey both forward momentum and the jarring vibrations of the wheels up and down on the cobblestone street. In combining these elements, the work creates a tension between the present and the past, as the older cobblestones are juxtaposed with the modernity of the background and the bicycle. Resembling the cobblestones in color and shape, the cyclist's flat cap identifies him as a Russian worker, and this contrasts with the aristocratic top hat depicted in the advertisement behind him. This more representational treatment of the cyclist as an ordinary man on his way to work, whilst echoing themes of the importance of the worker, sets itself apart from Italian Futurism, which focused on cycling as an aggressive sport - as seen in Boccioni's Dynamism of a Cyclist (1913), where a speeding cyclist becomes a violent vortex impelled across the pictorial plane.

Oil on canvas - The Russian Museum, St.Petersburg, Russia

Unique Forms of Continuity in Space

A man strides powerfully forwards, his form aerodynamically deformed by the speed at which he is traveling. As art critic Barry Schwabsky writes, "The fluid, rippling forms that make up this strange body are not its own; what Boccioni shows us, I believe, is the air moving around and about it as the body steps forward, seemingly against some great resistance. Boccioni's man has no shape of his own, but is molded instead by those forces in the face of which he determinedly proceeds". Geometrically rendered, helmeted and faceless with massive thighs and shoulders but armless, the figure seems both superhuman and robotic, a kind of machine man of the modern age. In exaggerating the dynamism of the body, Boccioni's form becomes a metaphor for progress acting against the forces of traditionalism and a testament to the role that machinery will play in the new age that he has envisaged.

Originally created in plaster, the work was not cast in Boccioni's lifetime and the bronze shown here is one of two cast in 1931. Frustrated by the limitations of canvas, Boccioni took up sculpture in 1912, noting that "these days I am obsessed by sculpture! I believe I have glimpsed a complete renovation of that mummified art". As this statement indicates, he felt that his approach, emphasizing what he called a "synthetic continuity" of motion was a radical transformation of the medium and opposed to the "analytical discontinuity" he found in the works of other contemporary sculptors including Frantisek Kupka and Marcel Duchamp. Despite his contempt for other types of sculpture, similarities can be seen between this work and other, more traditional, depictions including Auguste Rodin's Walking Man (1877-78) and the Winged Victory of Samothrace (c. 200-190 BC), both armless and headless figures striding forward.

Bronze - The Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York

Battle of Lights, Coney Island, Mardi Gras

Vibrantly colored, this kaleidoscope of whirling diagonals, cones, and elliptical forms depicts the amusements of Coney Island including its famous rollercoaster, which the artist described as "an intense arabesque...[its] surging crowd and the revolving machines generating... violent, dangerous pleasures". The fragments of brightly colored lights, rides, signs, and the Mardi Gras crowd create an intoxicating feeling of celebration. This work with its force lines, sense of motion and subject matter is clearly Futurist in style but in other ways it gently subverts the work of the group. The word 'Battle' in the title references the Italian canon which often depicted progress as a fight, but here, the fight is between each attraction for the attention of the working classes who frequent the amusements. In the same manner, Stella glorifies the proletariat but, in this image, they are at play rather than building the infrastructure of the future. Consequently, Stella places a uniquely American stamp on Futurism, portraying modern technology as enjoyable and entertaining.

This painting was both Stella's first major Futurist work and the first major American work in the style. Born and raised in Italy, as a young man Stella moved to New York to study medicine but, after two years, he transferred to the New York School of Art. In 1909 he returned to Italy where he met Boccioni, Carrà, and Severini and was influenced by Futurism, although he was also drawn to Fauvism's color palette and Cubism's fractured views. Describing his time in Europe, he noted that "Fauvism, Cubism, and Futurism were in full swing...[there] was in the air the glamor of a battle". Stella played a key role in introducing Futurism to America, associating with the photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz and collector Walter Arensberg and becoming close friends with Marcel Duchamp and Albert Gleizes. Shown at the 1913 Armory Show, Battle of Lights was initially viewed negatively by the public, but as art historian Sam Hunter writes, "Among the modern paintings at the Armory Show, Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase, Picabia's Procession at Seville and Futurist Battle of Lights, Coney Island came to exert the most seminal influence on American painters".

Oil on canvas - Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut

Città Nuova (New City)

This image is part of Sant'Elia's design for a new city and this reflects the architect's ideas of modernity. He expressed these in The Manifesto of Futurist Architecture in 1914, writing that "We must invent and rebuild our Futurist city like an immense and tumultuous shipyard, active, mobile, and everywhere dynamic, and the Futurist house like a gigantic machine". In this part of the design, elevators can be seen ascending the façade of the building, and modern modes of transportation, highways and trains, run alongside and into the complex. The building itself is multi-leveled and as well as more traditional vertical lines it is composed of elliptical and diagonal lines, which Sant'Elia wrote were "dynamic by their very nature".

Sant'Elia worked in the Milan public works department while still a student and was influenced by a number of architects including Adolf Loos, and Otto Wagner. He graduated with an architectural degree in 1912 and set up his own office where, along with finishing others' projects to make a living, he began work on this design. Exhibited at the Famiglia Artistica Gallery in 1914, his city was seen as a model of a new age.

His architectural concepts in the Manifesto were equally innovative, as architectural historian Reyner Banham calls them, "prophecies of...the essential philosophy of the International style...[and] the idea of mechanism...the Machine Aesthetic". Most of his designs were never built, as World War I erupted, and, like a number of Futurists, he enthusiastically enlisted, dying in battle in 1916 when he was 28 years old. His designs, nevertheless, preempted the styles of Art Deco and influenced later architects including Helmut Jahn, as seen in the James R. Thompson Center (1985) in Chicago and John Portman's Atlanta Marriott Marquis (1985). As Banham notes, "he was...the first to conceive the planning of the cities as fully three-dimensional structures."

Ink over black pencil on paper - Musei Civici, Como, Italy

Speeding Train

As a train travels diagonally towards the viewer, it begins to dematerialize, fracturing into elliptical and diagonal planes of varying degrees of transparency. The work conveys the experience of a train passing by closely, reflecting the overwhelming sounds, sights, and motion. At the center left of the canvas concentric circles spinning in widening arcs create a vortex of velocity that seems to bear down on the viewer. Futurist artists saw trains as symbols of modern dynamism, but Pannaggi's image also reflects Italy's efforts to modernize in the 1920s, as the rail system was electrified, allowing for record-breaking speeds.

The artist joined the movement in 1919 when he presented two of his Futurist paintings at Casa d'Arte Bragaglia where Marinetti and Balla praised then. In 1922 with Vinicio Paladini, he wrote the Manifesto of Futurist Mechanical Art, advocating for an aesthetic "Based on MACHINES...Gears wipe away the misty and indecisive from our eyes, everything is more incisive, decisive, aristocratic and sharp. We feel mechanically, and we sense that we ourselves are also made of steel, we too are machines, we too have been mechanized by our surroundings".

Oil on canvas - Fondazione Carima-Museo Palazzo Ricci, Macerata, Italy

Aeroritratto di Mussolini aviatore (aerial portrait of Mussolini)

Ambrosi was a second-generation Futurist who focused on Aeropittura (Aeropainting), a significant theme within the movement throughout the 1930s. In this image he combines an aerial landscape of Rome with the profile of Mussolini, which juts heroically from the buildings and streets. This represents Mussolini as part of the capital city, woven into the fabric of the country and important to its success. Many Futurists were closely associated with Fascism and this image is clearly propagandistic in tone.

Launched in 1929 with a manifesto, Perspectives of Flight, Aeropittura celebrated the technology and excitement of flying, something directly experienced by most aeropainters. The manifesto was signed by Benedetta Cappa, Fortunato Depero, Gerardo Dottori, Fillia, Marinetti, Enrico Prampolini, Mino Somenzi and Tato and these artists noted that "The changing perspectives of flight constitute an absolutely new reality that has nothing in common with the reality traditionally constituted by a terrestrial perspective". Interpretations of Aeropittura varied from realistic landscapes to dynamic and abstract compositions.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

Beginnings of Futurism

Futurism began its transformation of Italian culture in February 1909, with the publication of the Futurist Manifesto, authored by the poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. Although initially printed in La gazzetta dell'Emilia in Italy, it was reproduced a couple of weeks later on the front page of Le Figaro, which was then the largest circulation newspaper in France. The manifesto called for the glorification of progress, industry, and mechanization and the removal of old ideas and institutions. This was the first of many manifestos that the group published. Marinetti's ideas drew the support of artists including Umberto Boccioni, Giacomo Balla, Gino Severini, and Carlo Carrà, who believed that they could be translated into a modern, figurative art which explored properties of space and motion. The group was initially based in Milan, but the movement quickly spread to Turin and Naples, and over subsequent years Marinetti vigorously promoted it abroad.

While Marinetti was Futurism's leading writer, theoretician, and promoter, Umberto Boccioni was the artistic leader. In 1910, along with Balla, Carrà, Severini, and Luigi Russolo, he wrote the Manifesto of Futurist Painters, stating their desire to "fight with all our might the fanatical, senseless and snobbish religion of the past" and to "elevate all attempts at originality, however daring, however violent...[to] support and glory in our day-to-day world, a world which is going to be continually and splendidly transformed by victorious Science." The Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting (1910) followed, which rejected "bituminous tints", "linear technique", and the subject of the nude, in favor of "painting as a dynamic sensation".

In 1911 the group first showed their work publicly, in the Esposizione di Mostra d'Arte Libera (Exhibition of Free Art) in Milan. Not only did they want to promote the new movement, but were also motivated by a desire to raise money for the Casa di Lavoro (House of Work) that supported the city's poor and unemployed. The exhibition extended an invitation to submit work to "all those who want to assert something new, that is to stay far from imitations, derivations and falsifications". Many of the paintings displayed featured threadlike brushstrokes and the use of bright colors. Images depicted space as fragmented and fractured and subjects focused on technology, speed, and violence. Among the paintings was Boccioni's The City Rises (1910), exhibited under its original title Il lavoro (Work), a picture that can claim to be the first Futurist painting by virtue of its advanced, Cubist-influenced style. Public reaction was mixed. French critics from literary and artistic circles expressed hostility, while many praised the innovative content.

Influences on Futurism

The Italian group was slow to develop a distinct style. In the years prior to the emergence of the movement, its members had worked using an eclectic range of methods inspired by Post-Impressionism, and they continued to do so. Whilst studying in Rome in 1901, Severini and Boccioni visited Balla's studio where he introduced them to Divisionism. Developed from the color theory and Pointillism of Georges Seurat, in Divisionism the image was separated into stippled dots and stripes of pure color and these interacted optically to create the finished work. The use of bold color became very important to the Futurists, as art critic Henry Adam notes, the artists "in keeping with their Post-Impressionist antecedents, employed brilliant, electrifying, prismatic colors".

It was Cubism, however, that had the greatest impact on Futurist art, even though the Futurists felt it was too static in its treatment and subject. In 1911 a number of Futurists traveled to Paris, where Severini introduced Boccioni, Carrà, and Russolo to the city's leading artists, including Picasso and Braque. As a result of this encounter, the Futurists began to incorporate fractured planes into their work. Boccioni revised the three paintings of his States of Mind series (1911) and Carrà incorporated fracturing into Funeral of the Anarchist Galli (1910-11).

Pre-War Developments

Futurism came to wider public attention in 1912 with the First Exhibition of Futurist Painting at the Bernheim-Jeune gallery in Paris at which the group displayed a number of these early works. As art historian Lawrence Raney records, the style "prompted discussion that extended through every level of metropolitan culture, from elite literary reviews to mass circulation newspapers, in France, England, Germany, and Russia". The exhibition subsequently went on tour, traveling to London, Berlin, and Brussels.

The years 1913-14 were marked by an expansion of Futurism into sculpture, architecture, and music. In 1913, Boccioni used sculpture to further articulate Futurist dynamism with his work Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913) with sought to present vigorous action as well as ideas of the mechanized body. Luigi Russolo shifted from painting to creating musical instruments, and later wrote the manifesto The Art of Noises (1913). In 1914, the innovative Antonio Sant'Elia became the first architect to join the movement and Marinetti published the Futurist poem Zang Tumb Tuuum: Adrianople October (1914) the same year.

Despite all of this activity, the group had begun to diverge and fracture, signaling its end as a unified movement. Though World War I broke out in 1914, Italy remained neutral until 1915. In the interval, the focus turned from art to war, as Marinetti, Boccioni, and other Futurists used their events and performances to inflame crowds to anti-Austrian sentiment and issue passionate calls to intervention.

Concepts and Mediums

Dynamism

Futurist artists sought to create works that captured movement, or dynamism, as a way of representing the frenetic motion of modern life. This association between speed and modernity is reinforced by the Manifesto of Futurist Painters (1910) which notes that artists "must breathe in the tangible miracles of contemporary life - the iron network of speedy communications which envelops the earth, the transatlantic liners, the dreadnoughts, those marvelous flights which furrow our skies, the profound courage of our submarine navigators and the spasmodic struggle to conquer the unknown. How can we remain insensible to the frenetic life of our great cities...?"

Dynamism was usually depicted through fracturing of the image, energetic brushstrokes, compositional turbulence, and receding or emerging forms. Accordingly, Futurist art often focused on subjects that both moved rapidly and incorporated modern technology, from cars such as Russolo's Dynamism of an Automobile (1912-13) to cyclists as seen in Boccioni's Dynamism of a Cyclist (1913).

Modern Warfare

In the first Futurist Manifesto, Marinetti wrote, "We want to glorify war - the only cure for the world - militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of the anarchists, the beautiful ideas which kill". This reactionary statement followed from his belief that Europe and Italy's past should be violently swept away to make room for new ideas. He also saw modern technology as an instrument of war, writing, "a roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace."

Consequently, the depictions of dynamism developed in the pre-war years were readily applied to the conflict. As art historian Selena Daly writes, when World War I began, the Futurists "were terribly excited by the bombardments. They found this to be an inspiration also for their art and in very many ways putting into practice what they had preached". War and violence became a focus for their work as they followed Marinetti's advice to "try to live the war pictorially, studying it in all its forms". Works from this period include Severini's The Armored Train (1915) and Boccioni's Charge of the Lancers (1916). There are, however, fewer Futurist canvases from the First World War than might be expected and this is because many of the group joined the army as volunteers with Boccioni, along with Russolo, Sant'Elia, and Marinetti, serving in the Battalion of Volunteer Cyclists, focusing their attention on fighting rather than painting.

Photography and Film

The Futurist fascination with movement led to their interest in photography. Influenced by the motion studies of Eadweard Muybridge and Etienne-Jules Marey, the three Bragaglia brothers invented what they called photodynamism, photographs that showed a figure in motion from right to left with sections blurred to demonstrate movement. This is seen in Anton Giulio Bragaglia's Waving (1911). Balla was particularly enthusiastic about the technology, and some of his paintings evoke these photographs, with objects blurred by movement. This technique is reflected in the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting, which noted that "On account of the persistency of an image upon the retina, moving objects constantly multiply themselves; their form changes like rapid vibrations in their mad career. Thus a running horse has not four legs, but twenty, and their movements are triangular". Rather than perceiving an action as a performance of a single limb, Futurists viewed action as the convergence in time and space of multiple extremities.

The Bragaglia brothers were removed from the Futurists in 1913, primarily due to their promotion of photodynamism as an independent movement, although both brothers continued to work in a similar style from outside the official group. As a result of the explusion, Futurism ignored photography until the 1930s when a new generation of photographers emerged, emphasizing photomontage and multilayered negatives. The most prominent of these, Tato (Guglielmo Sansoni) wrote the Futurist Photography: Manifesto (1930) in conjunction with Marinetti. This suggested that "photographic science" should invade "pure art" and theoretically associated it with Fascism.

The Futurist obsession with movement made film an ideal medium for experimentation as well as fulfilling the group's criteria in terms of exploring new technology. The Futurists made a handful of films between 1916 and 1919, but unfortunately only Thais, filmed in 1916 by Anton Giulio Bragaglia, survives. Despite telling a conventional story of the period, the Futurist influence can be seen in the heavily stylized aesthetic and inclusion of significant abstract elements. The film sets, designed by Enrico Prampolini, utilized strong black and white geometric shapes as well as including symbolic elements and their appearance influenced the cinematic style of German Expressionism.

Literature

Futurism was a leading avant-garde movement in poetry and literature, as Marinetti explored new modes of literary expression, developing poetry that he called parole in libertà, or "words in freedom". Parole in libertà works eliminated punctuation, syntax, and adjectives, used only the infinitive form of verbs, and incorporated symbols. Marinetti put these ideas into practice in Zang Tumb Tuuum: Adrianople October (1914), an account of the pre-World War I Battle of Adrianople, which he covered as a journalist. As scholars Caroline Tisdall and Angelo Bozzola explain, "as an extended sound poem it stands as one of the monuments of experimental literature, its telegraphic barrage of nouns, colors, exclamations and directions pouring out in the screeching of trains, the rat-a-tat-tat of gunfire, and the clatter of telegraphic messages". The poem also influenced graphic design, as Tisdall and Bozzola note, "through the revolutionary use of different typefaces, forms and graphic arrangements and sizes." Following on from Marinetti's work, Balla created phonovisual constructions and, later, Fortunato Depero created onomalingua, an abstract language of sounds.

International Futurism

Czech artist Růžena Zátková, lived in Rome for a decade and studied with Balla. Art critic Jan Velinger described her sculpture Pile Driver (1916) "as a piece that captures the frozen rhythm and dynamic of the machine and modern industry". She became primarily known, however, as a pioneer of Kinetic Art, connected to the Russian avant-garde. In the United States, Joseph Stella's Battle of Lights, Coney Island, Mardi Gras (1913-14) is considered part of the Futurist canon, but his subsequent works were equally informed by Fauvism's color palette and Cubism's multiple perspectives.

Interest in Futurism began in Japan with awareness of Marinetti's work and the various manifestos published by the group around the First World War. In 1920 Seiji Tōgō, Gyō Fumon, and Tai Kanbara formed The Futurist Art Association and held the first Futurist Art Group Exhibition. Fumon's Deer, Youth, Light, Crossing (1920) is described by contemporary art historian Toshiharu Omuka as "violent use of colors and brush work to express dynamic movement" and this work exemplifies the Japanese treatment. The leaders of Russian Futurism, David Burliuk and Viktor Palmor, visited Japan in 1920 and their impact resulted in Japanese modernism becoming, as Omuka notes, "a curious and complicated amalgamation of Italian and Russian Futurism".

While Italian Futurism has been credited with inspiring Russian Futurism (also known as Cubo-Futurism), the movement, including artists such as Kazimir Malevich, Lyubov Popova, Natalia Goncharova, and David Burliuk, as well as the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky vehemently rejected this notion. Originating in the literary group Hylaea, Russian Futurism was less visual and more literary-based than their Italian counterparts and text and typography featured heavily in much of their work. The group was active between approximately 1912 and 1916. Whilst Russian Futurism developed its own styles and ideas, emphasizing a return to Russian traditions whilst embracing modernity, it overlapped with Italian Futurism in many ways, particularly its depictions of dynamism and urban life and its celebration of the worker.

To suggest that the Italian movement had no influence on the Russian group is simplistic. Members of the Russian Futurists traveled throughout Europe between 1909 and 1913, with poets Alexander Blok, Valery Bryusov, Andrei Biely, Max Voloshin, and Nikolai Gumilev all visiting Italy during this period. Bryusov, particularly, formed links with Italian Futurism and had poems published by Marinetti. Boccioni also spent time in Russia. As such, Marinetti was eager to claim the Russian movement as a direct descendent of his own, writing that, "There can be no argument that the word Futurism (Futurists, Futuristic) appeared in Russia after my first manifesto was printed in Figaro and reprinted by the most important newspapers throughout the world and of course, by Russian newspapers and journals". This claim caused a conflicted and uneasy relationship to exist between the two groups and when Marinetti made his first trip to Russia in 1914, he was met with hostility and disdain.

Later Developments - After Futurism

Boccioni and Sant'Elia died in the First World War, whilst Carrà suffered a nervous breakdown and, while convalescing in a military hospital, met Giorgio de Chirico, who was also recovering. The two men went on to become active in the Metaphysical School of painting. Severini, who remained in Paris throughout the war, had, by the 1920s, turned toward still life and Interwar Classicism. Following the war, Marinetti formed the Futurist Political Party, allied with Benito Mussolini's Fascist movement. After the party's political defeat, he tried to promote Futurism in other ways but was met with a negative reception as the two movements had become problematically associated. This was compounded by Dada circles using the slogan, "The Futurist is dead. What killed it? Dada".

In the 1920s the movement, though considerably diminished and confined to Italy, attracted new artists including Fortunato Depero, Gerardo Dotori, and Ivo Pannaggi. Contemporary scholars have called this era Second Futurism, and as art critic Roberta Smith notes their work became "more consistent and decorative". In the interwar period, the group created ceramics, toys, posters, advertisements, and set designs. At the same time, Futurist painting became fascinated with the view from airplanes or high-rise buildings, an idea known as Aeropittura (Aeropainting), and this perspective is prevalent throughout later Futurist works.

Legacy

From around 1912 to 1920, Futurism had a profound influence on artists and art movements. German Expressionists adopted Futurist elements, as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner explored force lines to depict the movement and volatility of crowd scenes and Franz Marc incorporated them in works such as Animal Fate (1913) to lend dynamism to a subjective vision. George Grosz's canvas Explosion (1917) also shows many of the hallmarks of Futurism. In England Futurism had a significant impact on the development of the Vorticist movement, including philosopher T.E. Hulme, poet Ezra Pound and artists Wyndham Lewis, David Bomberg, and Jacob Epstein. In the United States, it influenced the development of modernism, primarily through Joseph Stella's work. Dada is thought to have been affected by Futurist sound poems and performances.

Antonio Sant'Elia's designs pre-empted Art Deco styles and inspired American architects Helmut Jahn and John Portman, as well as filmmakers such as Fritz Lang and Ridley Scott providing the aesthetic for films including Metropolis (1927) and Bladerunner (1982). More recent scholarship has taken a fresh look at Futurism and major exhibitions such as the Guggenheim's Italian Futurism, 1909-1944: Reconstructing the Universe in 2014 both reflect and drive the critical re-evaluation of the movement.

Useful Resources on Futurism

- Futurism (Movements in Modern Art)Our Pick

- Futurism: An Anthology (Henry McBride Series in Modernism)

- The New Tendency in Art: Post Impressionism, Cubism, Futurism (1913)Our Pick

- The Other Futurism: Futurist Activity in Venice, Padua, and Verona (Toronto Italian)

- The Turn of the Century: The First Futurists (American University Studies)