and set forth on my journey.

I shall see the famous places in the Western Land."

Summary of Ukiyo-e Japanese Prints

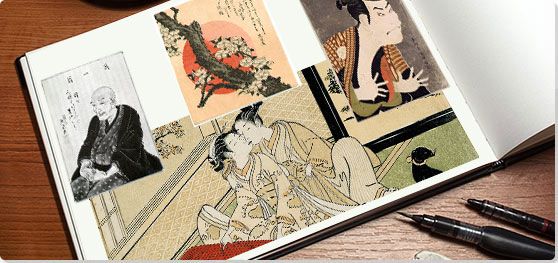

Ukiyo-e, often translated as "pictures of the floating world," refers to Japanese paintings and woodblock prints that originally depicted the cities' pleasure districts during the Edo Period, when the sensual attributes of life were encouraged amongst a tranquil existence under the peaceful rule of the Shoguns. These idyllic narratives not only document the leisure activities and climate of the era, they also depict the decidedly Japanese aesthetics of beauty, poetry, nature, spirituality, love, and sex.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The people and environments in which the higher classes emerged themselves became the popular subjects for ukiyo-e works. This included sumo wrestlers, courtesans, the actors of kabuki theatre, geishas and teahouse mistresses, warriors, and other characters from the literature and folklore of the time.

- By combining uki for sadness and yo for life, the word ukiyo-e originally reflected the Buddhist concept of life as a transitory illusion, involving a cycle of birth, suffering, death, and rebirth. But ironically, during the early Edo period, another ideograph which meant "to float," similarly pronounced as uki, came into usage, and the term became associated with wafting on life's worldly pleasures.

- Ukiyo-e prints were often depicted on Japanese screens or scrolls, lending to their narrative feel. Although different artists brought their own signature styles, the pictures were weaved by a common look and feel that utilized aerial perspectives, precise details, clear outlines, and flat color, furthering the earlier yamato-e tradition of Japanese art.

- Many subgenres blossomed beneath ukiyo-e's artistic umbrella to become known as its primary motifs. This included imagery of beautiful women, erotica, portraits of subjects with big heads, bird and flower pictures, and renditions of iconic natural landscapes such as Mount Fuji.

- Ukiyo-e was one of the first forms of Japanese art that found its way across the seas to Europe and America with the opening of trade between the countries. The influence that this exposure had upon the West became known as Japonism, defined by an interest in the aesthetics of the style that would go on to profoundly influence many Western artists and movements such as Impressionism, Art Nouveau, and Modernism.

- While in the beginning, ukiyo-e's was defined by a collaborative four person woodblock printing process, the movement's artists would soon come to revolutionize the creative use of printing through experimentations with material, color, mineral, and line to become an ancient forebear to the country's contemporary art movements such as Superflat.

Overview of Ukiyo-e Japanese Prints

Announcing, “I used to call myself Hokusai, but today I sign my self ‘The Old Man Mad About Art,’” Katsushika Hokusai created his One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji. The inexhaustible master was 74.

Artworks and Artists of Ukiyo-e Japanese Prints

Two Lovers

This print, deploying an aerial perspective which was a noted feature of Japanese art, depicts two lovers, a samurai warrior whose sword can be seen in the foreground lying beside him, and a woman whose discarded musical instrument lies in the right middle distance with the diagonal of its neck extending toward the right corner. Above the musical instrument, an outer robe seems to float through the air as if it had just been cast off. The room is depicted in elemental forms by means of horizontal and vertical lines that intersect at the couple, whose figures begin to flow together in the curvilinear forms of their figures, and robes. On the left an external balcony can be seen through an open panel.

Moronobu's family was in the textile business and he applied his knowledge in the pattern of the robes, but also in his understanding of how fabric moves when on the human body. His mastery of line originated in his understanding of calligraphy, as shown here in his varying thickness of preciseness to create the figures and their surroundings. As the lovers' sleeves and robes move in parallel lines, their fabric and figures begin to merge where their bodies meet. This is an early example of shunga and may have been the frontispiece for a 12 print series depicting the dance of sexual relations, as the frontispiece was often more decorous and posited as a kind of prelude.

Polychrome woodblock print; ink and color on paper - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

Poem by Fujiwara no Motozane (c. 860) from the Series Thirty-Six Poets

In this print, a young woman, holding a bamboo rod in her left hand used to hang clothes upon a line, turns to look over her shoulder and lifts her right hand as if to stop her son from chasing a small chick. Along a fence in the middle left of the print, white unohana flowers bloom, indicating that it is early summer. A poem by Fujiwara no Motozane, one of the Thirty-Six Immortal Poets included in Harunobo's series of images, is written in a cloud-like shape along the upper part of the print. The words are translated by Jack Hillier as:

"Blossoming now in our mountain village,

the unohana flowers look like snow

still lingering on the hedge."

The flowing lines of the figures energetically curve from right to left and contrast with the flowering branches, curving from left to right, to convey graceful movement. Horunobu often blurred exterior and interior worlds to create a feeling of natural harmony, but his pioneering naturalism, depicting an actual mother and child in ordinary activity, made his work influential. Ukiyo-e's frequent depictions of a mother with her child, emphasizing line and design to convey emotion and relationship, influenced the work of Mary Cassatt as seen in The Child's Bath (1893).

The print also exemplifies Horunobu's subtle use of color, drawn from the Torii School's Benizuri-e "rose prints" application in which a limited number of colors, often including green and pink, were applied to the printing process. These varying shades both unify the composition and create a sense of vibrant life.

Polychrome woodblock print; ink and color on paper with embossing (karazuri) - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

Interior of a Bathhouse

This print depicts a number of women, nude or partially robed, in various activities of bathing. Bathing was an important ritual in Japanese culture and communal bathhouse scenes were incorporated into ukiyo-e's everyday subject matter as one of the few to include treatment of the nude. The print is a double sheet print, with four women on the left side and four on the right, one of whom is washing a baby. In the upper center of both panels, a washing area is partially screened, showing a woman's lower torso as she washes herself. To the left, a small open panel and another, even smaller above it, captures a glimpse of the men's bathing area. The water buckets, some filled, others tipped over and empty are arranged in a diagonal line, that echoed by the diagonals of the flower board creates a vertical movement from the kneeling women in the foreground toward the partially screened bathing area. The composition's use of vertical and horizontal lines contrasts with the curvilinear figures, each of which is individualized, both in physical features and activities.

This particular print was formerly owned by the Impressionist painter Edgar Degas, who was influenced not only by its vertical and horizontal composition, but the poses of the figures, caught in ordinary activity that is both intimate and revealing. Kiyonaga made several variations of this image, and this print is a second variation as the woman standing on the right sheet has been changed toward a more modest pose.

Woodblock print (nishiki-e), ink and color on paper - Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

Poem of the Pillow

Poem of the Pillow included 12 images in a folding album, and this is the tenth print in the series depicting two lovers at a teahouse. The woman reclines with her back to the viewer, as her torso curves to her nude left leg, revealed as her clothing slips down. In front of her, a man leans in for a kiss, his form flowing above hers, as his bare legs meet hers on the left. Through the transparent black and white fabric of his robe, their bodies meet, as her left foot reaches over behind his leg. The subtle color palette of the red and black patterns conveys a depth of feeling, while in the background a balcony railing, a yellow shutter on the right, and a green plant extending above the railing create a sense of privacy, as the tea and bowl containing food on the right create a sense of intimacy.

More than half of Utamaro's prints were shunga, and he is considered by Japanese art historians, to be the great master of the genre. Poem of the Pillow, or "Utamakura" was accompanied by a poem from a classical Japanese poet, which read, "Its beak caught firmly / In the clamshell / The snipe cannot fly away / Of an autumn evening." Rather than a particular image, the plethora of erotic imagery in shunga prints had a strong influence on European artists, particularly Audrey Beardsley, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, and Pablo Picasso. The art critic and collector Edmond de Goncourt described how the sculptor Auguste Rodin, "asks to see my Japanese erotica, and he is full of admiration before the women's drooping heads, the broken lines of their necks, the rigid extension of arms, the contractions of feet, all the voluptuous and frenetic reality of coitus, all the sculptural twining of bodies melted and interlocked in the spasm of pleasure." This unabashed treatment of sexual subjects was carried over into the spirit of European art.

Color woodblock print - The British Museum, London

Three Beauties of the Present Day

This nishiki-e, or full color print, depicts three women noted for their beauty, on the left, Takashima Hisa, and on the right, Naniwa Kita, both of whom worked as waitresses in their family's teahouses. Tomimoto Toyohina, a geisha, is depicted in the middle. Each woman wears her family crest, like the oak leaf motif on Hisa's left upper arm, visible in the lower left of the canvas, and reflects the artist's innovative subject matter in portraying three women from the urban population, rather than the traditional subject of courtesans of the pleasure district.

The work exemplifies his pioneering style both in developing nishiki-e, and in adding mica dust, as seen in the shimmering effect of the background. The women, in the ōkubi-e (big-head) style, are individualized, as the print registers subtle differences of personality, and the rivalry between the two teahouses is conveyed in the somewhat confrontational face-to-face gaze of Hisa and Kita. In Japan at the time teahouses were ranked and both Kita and Hisa drew many to their family's teahouses, fostering a kind of competition that extended to the different districts where each teahouse was located. Utamaro was to depict the three women in subsequent prints, and this image became so popular that other artists also portrayed the trio.

The artist's triangular composition, referencing the tradition of The Three Vinegar Wine Tasters (16th century), a painting which depicted Buddha, Laozi, and Confucius to represent the essential unity of the three religions they founded, is meant to emphasize the unity of beauty, while acknowledging its subtle individuation. As a result of Utamoro's influence, many ukiyo-e artists adopted triangular composition in the years that followed. Utamaro's depictions of beautiful women, employing strong line and flat areas of color, influenced European artists as varied as James Abbott McNeill Whistler and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec.

Nishiki-e color woodprint block - Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts

kabuki Actor Ōtani Oniji III as Yakko Edobei in the Play The Colored Reins of a Loving Wife

This dramatic print depicting the famous actor Otani Oniji II in a three-quarter view, uses bold strong lines and simplified elements to convey a feeling of ruthless malevolence. Playing the part of an evil servant, Yakko Edobei, who was only too happy to carry out his samurai master's orders, the actor here becomes synonymous with his role as he is caught in mie, a moment of extreme emotion with the dramatic facial expression that characterized kabuki. The white of skin, as his grasping hands erupt from his body and the white of his bare chest curves up to his aggressive leering expression, is highlighted by the surrounding black outlines of his robe and hair. Against a grey background, the figure is flat, almost cutout, and modernist in its realistic psychological portrayal.

Reduced to essential elements, both the actor and the role he is playing, as shown in his clothing and the crest he wears, would have been immediately recognizable to the viewer.

Sharaku is a somewhat mysterious figure, unassigned to any school and his identity, his date of birth, and death uncertain. He was active in ukiyo-e only from 1794-1795, and most of the 140 prints attributed to him portray actors. In his own time, his work provoked attention but was also somewhat unpopular, due to his bold and often unflattering realism. Yet, his energetic and reductive compositions with their unflinching insight have subsequently led to his being considered the great master of yakusha-e. Henri Toulouse-Lautrec was particularly influenced by Sharaku's boldly profiled and individualized portraits, and adopted a similar treatment, including the exaggerated grimaces, in depicting the denizens of the Moulin Rouge and other Parisian night spots.

Polychrome woodblock print; ink, color, white mica on paper - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife

The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife, also known as Girl Diver and Octopuses, is a woodblock print that was included in a three-volume book of erotica called Kinoe no Komatsu and has become Hokusai's most famous shunga design. The work depicts a female ama, or shell diver, entangled in the limbs of two octopuses. The large octopus performs cunnilingus on her largely emphasized genitals, while the smaller octopus fondles her mouth and left nipple. The woman seems to derive great pleasure from the exchange, denoted by her relaxed mien and blissful face. In the text above Hokusai's image, the big octopus says he will bring the girl to the dragon God of the sea, Ryūjin's, undersea palace.

The piece is said to have derived inspiration from a popular story of the time that appeared often in ukiyo-e art. In the tale, Princess Tamatori is a young shell diver married to Fujiwara no Fuhito, searching for a pearl stolen from his family by Ryūjin. As she dives beneath the water to help reclaim the pearl, an army of sea creatures pursues her. She absconds the pearl by cutting open her breast and hiding it within but dies from her wound soon after reaching the surface.

Hokasai's artistic peer Yanagawa Shigenobu also created a similar image of a woman in sexual relations with an octopus in his collection Suetsumuhana in 1830. The work has also influenced other artists such as Felicien Rops, Auguste Rodin, Louis Auccon, Fernand Khnopff, and Picasso who painted his own version in 1903. It is also cited as a forebear to contemporary "tentacle erotica," which has appeared in Japanese animation and manga since the late-20th century.

Woodblock print on paper - Included in the book Kinoe no Komatsu (English: Young Pines)

Under the Wave off Kanagawa (also known as The Great Wave)

This print, which is internationally recognized, depicts a great wave (the alternative title for this work is The Great Wave), painted in Hokusai's favored Prussian blue, its crest breaking in stylized depictions of white foam. The wave almost fills the left side of the canvas, and its curvilinear energy seems to threaten to engulf Mount Fuji. This engulfing effect is created by the artist's subtle use of perspective and his deploying a horizon posited in the lower third of the painting. Among the waves, a number of Japanese boats can be seen, their long curved forms, distinguished by their planes of contrasting color, echoing the lines of the waves. The scene has an impending energy, depicting the moment just before the wave breaks. Mount Fuji, the highest mountain in Japan, was traditionally felt to be a symbol of immortality, a totem of kami, but its diminished form here, as the wave towers above it, suggests that the idea of immortality is as transitory as the boats about to be swamped and torn apart.

Art curator Timothy Clark called One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji, from which the print was taken, as "one of the greatest illustrated books." The series was produced in three volumes and actually included 102 views of the mountain. It was produced at a time when Hokusai, who often changed his artist name, was calling himself Gakyō rōjin ("Old Man Crazy to Paint"), or Manji ("Ten Thousand Things", or "Everything"), showing his intent to create a comprehensive tour de force. Elements of Hokusai's work, innovatively varied and prolific, influenced countless European artists like Claude Monet who had a print of The Great Wave displayed at his home in Giverny. Paul Gauguin, Auguste Rodin, Edgar Degas, Gustave Klimt, Édouard Manet, Vincent van Gogh, and Franz Marc collected his prints. Degas was influenced by Hokusai's depiction of the human figure in non-posed and ordinary activity, while his curvilinear forms and wave-like compositions influenced the development of Art Nouveau.

Polychrome woodblock print; ink and color on paper - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

Ejiri, Suruga Province (A Sudden Gust of Wind)

This print shows a number of travelers on a road curving through reed-filled fields near a lake with Mount Fuji outlined on the left. The woman on the lower left is hit by the shock of the wind as her clothing swirls up, shrouding her face. The papers she has been carrying are torn from her hands into the center of the canvas, mingling with the leaves torn from the two thin trees. Bent and pushed by the wind, a man to her right hangs on to his hat, while another looks up at his hat carried up into the air on the far right. The two diagonal verticals of the thin trees on the left tilt with the wind emphasizing the movement that Hokusai captures, as his wryly observed depiction of ordinary people intent on their purposes disrupted by a ordinary gust symbolizes the disruptive force of nature. The curving landscape that folds in waves of repeating lines and colors conveys a sense of vastness, and the light colored horizon, no more than a wash of color and a few simple lines, evokes the serene and eternal presence of Mount Fuji while the people try to keep themselves from flying away like the materials that they have been carrying.

This print has continued to influence contemporary artists. Jeff Wall's A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai) (1993), a photograph in a light box, references Hokusai's print by showing four figures beneath two thin trees, as they are struck by the wind, in a modern industrial farming landscape.

Polychrome woodblock print; ink and color on paper - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

Flock of Chickens

This print by the master Hokusai, realistically depicting different breeds of chickens all huddled together, creates a circular swirl of form, as the birds become a wave of color and curvilinear flow. Hokusai's influential work was itself inspired by European models, in this case by scientific illustrations of different species. Yet his emphasis on design, the dramatic red, white, and black color palette with variations of brown and gold, exemplify Japanese aesthetic principles, as his kachō-ga imagery here becomes an image of birds arranged as if they were variations of one blossoming form. The curving lines of the roosters' tail feathers both create a sense of movement and unify the image, strongly outlined by black against the blue background. These prints were often later produced as handheld paper fans, reflected through the compositional shape in this work.

Hokusai's kachô-ga prints had a great influence on European designers and artists in the mid-19th century, as seen as Felix Bracquemond's Service Rousseau (c. 1867) tableware inspired by Hokusai's manga images depicting many species of birds and flowers.

Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper - National Museum at Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Specter from the Story of Utö Yasutaka

This triptych, depicting a scene from the Story of Utö Yasutaka (1807) by Santö Kyöden, creates a dramatic panorama as an animated human skeleton fills the far right panel and extends, menacingly, in the middle panel, to tower over the huddled Oya Taro Mitsukuni and his companion. In the left panel, Princess Takiyasha holds a scroll from which she recites the spell to call up the skeleton. The Princess was the daughter of a warlord who had been killed while rebelling against the emperor, and Mitsukuni had been sent by the emperor to take over the castle. The diagonal lines of the floor that run from the left panel to the right create movement, drawing the viewer's eye to the skeleton on the right, and unifying the three panels. The hanging drapes in the left panel extend into the center panel, further emphasizing the huddled fear of the two men, cowering, as Mitsukuni turns a white face toward the skeleton.

Kuniyoshi combines a traditional story with a modern knowledge of anatomy, as his accuracy, derived from Western anatomical drawings, is combined with a Japanese sense of form. The cropping in the right panel creates a sense of dread overflowing the frame. Kuniyoshi was known for combining scenes from traditional Japanese culture and folklore with Western elements, in order to create psychologically compelling narratives.

These narratives, drawn from Japanese literature, folklore, and history, were a common theme of ukiyo-e, whether in a single image portraying an actor in a kabuki role from a story that would be immediately recognizable to the audience or in a work like Hokusai's One Hundred Ghost Tales (1833).

Color woodblock print - Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Plum Estate, Kameido (Kameido Umeyashiki)

This print from the famous series, One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (1856-1859), depicts a plum garden seen through the branches of the Sleeping Dragon Plum, a famous and sacred tree in Tokyo, whose white double blossoms were believed to drive away darkness. Other plum trees with the early buds of spring extend into the distance where a number of figures can be seen along the horizon, where a light sky darkens into red in the upper third of the print. The artist innovatively used the vertical orientation of a portrait print, and an exaggerated perspective that creates a cropped close-up of the Sleeping Dragon Plum. The composition becomes almost abstract, and the red sky with the sign in the upper left and the seals in the upper right further flattens the pictorial plane. The somewhat somber color palette, and shading on the wide branches of the framing tree, convey the bittersweet aesthetic of traditional Japanese art, as the somber, aged tree, frames the viewing of the plum blossoms associated with spring and romantic feeling.

One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, which actually included 119 landscapes, was one of Hiroshige's final works and was commissioned to feature the rebuilding of the city after the 1855 earthquake. Vincent van Gogh was greatly influenced by Plum Park in Kameido, painting a copy of it in 1877, though, noting the somber effect of the original, he altered the colors toward a more vigorous and youthful effect.

Woodblock print - Brooklyn Museum of Art, Brooklyn, New York

Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake

This iconic print depicts a number of people crossing the Shin-Ōhashi wooden bridge built in 1694 and spanning the Shimoda River, as they are caught in a sudden rainstorm. The closest figures, two women, take shelter under their umbrellas, as a number of men use their hats or capes for protection from the rain, its dark diagonal streaks vertically intersecting the print. A single figure can be seen on the left trying to push his log raft down the river to safety. The innovative skill of the print is reflected both in the falling rain, created by making parallel lines in varying directions, and by the use of bokashi, a printing technique which required inking a wet woodblock by hand, creating depth with the ink gradations and seen here in both the dark blue of the waters under the bridge and the slightly darker blue band of the storm at the top. Ukiyo-e prints often depicted the theme of sudden gusts of wind or rain showers, showing nature's constant presence by its unpredictable effect upon human activity.

Hiroshige's aerial perspective, his diagonal horizon well above center, his use of negative space, devoid of figures or detail, and large areas of color influenced many Western artists. Whistler created a number of paintings like Nocturne: Blue and Gold - Old Battersea Bridge (1872) that depicted a bridge deploying Hiroshige's composition and reductive palette, leading to the development of Tonalism. The Impressionists and Post-Impressionists were also influenced by the Japanese artist as seen in van Gogh's Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige) (1887).

Polychrome woodblock print; ink and color on paper - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

Woman At Her Bath

This iconic example of shin-hanga, or "new woodblock prints," depicts a nude woman at her daily bath, deep in thought, kneeling on the wet floor and wringing out a blue and white washcloth into a basin. Her body's flat plane of light color is softly, but precisely outlined against the yellow and pink partition behind her, where to the right, her robes are lying on a green floor.

Shin-hanga revived the traditional ukiyo-e collaborative process and also portrayed traditional ukiyo-e subjects, as seen in this bijin-ga print, yet at the same time the movement incorporated elements of Western art, as seen in the realistic depiction of a nude in naturalistic light with soft colors. The work also creates a feeling of individual mood and a compelling sense of privacy. The works of Utamaro, Hokusai, and Harunobu influenced Goyō when he created this work at the request of the publisher Watanabe Shōzaburō, who had coined the term shin-hanga. A perfectionist who supervised the production process for his prints and suffering from severe ill health, Goyō was to complete only fourteen prints before his premature death, though his work became viewed as setting critical standards for printing quality.

Color woodcut print - Library of Congress, Washington DC

Beginnings of Ukiyo-e Japanese Prints

Precedents: Yamato-e

Yamato-e, or classical "Japanese style" painting, developed in the 12th century. With its aerial perspectives, precise detail, clear outlines, and flat color, the art form existed in contrast to other styles of Japanese painting that reflected the influence of the Chinese. Japanese aesthetics were often dominated by Chinese styles, as shown in the Kanō School's primacy in the late 1400's, where it was known for its screens depicting landscapes on gold leaf backgrounds, created for the castles of feudal lords. At the same time, other schools arose to advocate Japanese styles and subjects. In the mid-1400s, the artist Tosa Yukihoro established the Tosa School, which furthered yamato-e, portraying stories from Japanese history and classical literature.

One of the earliest examples of yamato-e was the illustrated scroll of the Tale of Genji (11th century), thought to be the first novel ever written anywhere, by Murasaki Shikibu, a woman serving in the Heian court. Yamato-e emphasized the depiction of everyday details and people, as well as stories that had a deep connection to Japanese culture.

Edo Period (1603-1868)

During the Edo period, called such because Japan's capital had been moved to Tokyo (then called Edo), the country was under rule by the Tokugawa shogunate. This military regime enforced social segregation by emphasizing a hierarchal class system with warriors at the top, followed by farmers, craftsmen, and then merchants at the bottom. The regime also set aside certain walled areas in the cities where theatres, teahouses, and brothels were licensed and which came to be known as the "pleasure districts." It was a relatively peaceful time domestically and isolationist in relationship to the rest of the world. As a result, art that reflected this decidedly Japanese lifestyle found a new audience with a rising middle class. Ukiyo-e was born as an evolution of yamato-e, one in which the new lifestyle was emphasized and celebrated.

The subjects of these worldly pleasures, as well as their inhabitants such as famous courtesans, kabuki actors, and the like became the preferred creative fodder of ukiyo-e prints. The prints were popular 'low' art forms, created for the merchant class and the urban working population, but soon came to be considered masterful works of art.

Iwasa Matabei was a well-known painter of works depicted on byobu during this time. Though trained in the Kanō School, the Tosa School's traditional Japanese subjects and styles primarily influenced his mature work. His portrayals of geishas, hostesses who entertained by playing instruments, dancing, and reciting classical Japanese poetry, as well as the leisure life of the middle class became early examples of ukiyo-e painting.

Another artist, Hishikawa Moronobu, is considered to be the first great master and originator of ukiyo-e prints because of the book illustrations he began making in 1672. As color printing had not yet been invented, his prints were primarily monochromatic, though he also hand-painted some of them. He brought together the disparate elements of preceding ukiyo-e imagery and subject matter and formalized the art form with his mastery of line derived from calligraphy. His visuals included street scenes of ordinary life, images of reference to famous stories, poems, or historical events, and landscapes, images of beautiful women, and erotic prints. As a result, he is considered to be both the last of the proto-ukiyo-e artists and the first true ukiyo-e artist.

Ukiyo-e remained the dominant art form during the last century of the Edo period.

The Process of Ukiyo-e

Ukiyo-e depended upon collaboration between four people. The artist, using ink on paper, drew the image that was then carved by a craftsman into a woodblock. A printer then applied pigment to the woodblock, and a publisher oversaw and coordinated the process and marketed the works. Ukiyo-e were most commonly produced as a sheet of prints, which were so inexpensive that many could afford them. They also were collected in books, called e-hon. Sometimes, a print might be made using two or three sheets of paper, creating a triptych effect. Portraits used a vertical format, landscapes a horizontal format, but occasionally, vertical and narrow prints would be made, creating the effect of a scroll that would be displayed on columns or pillars.

Nishiki-e "Brocade Prints"

Suzuki Horunobu revolutionized ukiyo-e when in 1765 he invented the process to make nishiki-e, or "brocade prints," that made possible a full employment of color. The process involved making a series of woodblocks, all bearing the same image, and then a single color being applied to each block, so that the color on the final print was the result of layers of pigment. The pigments used were vegetable-based and water soluble and resulted in a subtle and rich palette. As many as 20 woodblocks might be used, each employing a different color, to print a single image on handmade paper. Horunobu's work influenced countless ukiyo-e artists.

Ukiyo-e Schools

Most ukiyo-e artists not only studied under a particular master but also would take the name of that master. Between 1672 and 1890 thirty ukiyo-e schools developed, each representing the particular style of its founder as well as several generations of its subsequent artists. The existence of these various schools overlapped throughout the years but the most important schools were the Torii School, the Katsukawa School, and the Utagawa School.

Torii School (1670-1815)

The Torii School began in the early-18th century with the works of Torii Kiyonobu I, who was a student of Moronobu. Kiyonobu I came from a family of prominent designers of kabuki promotional materials, and due to his own theatrical experience and interest, the Torii School pioneered the subject of kabuki theatre, which became one of the dominant themes of ukiyo-e prints. The school's style emphasized kabukian drama and its actors with their generalized appearances through bold designs with thick, energetic lines.

The Torii School became the dominant style of the 1700s as a new generation of artists came to the forefront. The school was innovative in using urushi-e prints, where the ink could be mixed with glue to create a lacquer effect or where mica or metal dust would be added to create a shimmering quality. They also explored Benizuri-e prints, "crimson printed" or "rose prints," in which a limited number of colors, often including green and pink, were applied to the printing process.

Noted artists associated with the Torii School included Suzuki Harunobo, who invented nishiki-e brocade prints, Kitagawa Utamaro, and founder Torii Kiyonaga. All three artists became celebrated for their bijin-ga prints, depicting beautiful women.

Katsukawa School (1750-1840)

The Katsukawa School, founded by Miyagawa Shunsu around 1750, was the first to portray kabuki actors in a way that departed from generic depiction and emphasized their individual characteristics and personalities. Katsukawa Shunshō pioneered these recognizable portraits, sometimes portraying actors in their dressing rooms.

A more realistic depiction of people carried over into other genres of ukiyo-e, as seen in Katsushika Hokusai's famous images of ordinary people in everyday life. Under the artist name Shunro early in his career, Hokusai was a member of the Katsukawa School. However, he innovatively began to explore the perspective and shading of Western art in his prints, resulting in his expulsion from the school. Hokusai described this significant event: "What really motivated the development of my artistic style was the embarrassment I suffered at Shunko's hands." Relentlessly innovative, he went on to create over 30,000 works and in the course of his long life took 30 artist names. He first became famous for his manga, which were books that contained woodblock prints of his sketches that art critic John-Paul Stonnard has described to contain, "every subject imaginable: real and imaginary figures and animals, plants and natural scenes, landscapes and seascapes, dragons, poets and deities combined together in a way that defies all attempts to weave a story around them."

Utagawa School (1770-1860)

The Utagawa School was founded by Utagawa Toyoharu in the 1760s and lasted into the 1850s, being in effect the last great school of ukiyo-e. Toyoharu was known for incorporating the perspective of Western art into his prints, like Perspective Pictures of Places in Japan: Sanjūsangen-dō in Kyoto, (c. 1772-1781) and a number of his students continued the exploration. Some 400-500 artists were either members of the school or associated with it, and the school created a majority of the known surviving ukiyo-e prints. By the mid-19th century, the school's prodigious production resulted in a kind of stereotypical portraiture, depicting lantern-jawed and somewhat exaggerated noses, resulting in criticism and a sense of ukiyo-e's decline. The renowned Hokusai was even to protest to his publisher that the woodblock carver kept altering the noses of his figures. Nonetheless the school became the best known of all ukiyo-e schools because it included the artists Toyokuni and Utagawa Hiroshige. Hiroshige became known as one of the all-time great masters of ukiyo-e who revived the art with his focus on serial views of landscape and scenes of ordinary life.

Ukiyo-e Japanese Prints: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Ukiyo-e was known for a number of genres depicting certain aspects of Japanese life. These included bijin-ga, shunga, yakusha-e, kacho-ga, and landscape.

Bijin-ga

Bijin-ga, meaning "beautiful person picture," was a dominant genre of ukiyo-e. Early prints often depicted famous courtesans who were often viewed as celebrities, but subsequently, artists like Utamaro would portray women who were known for their beauty from the urban population. Some of the other great masters of the genre were Suzuki Harunobu, Keisai Eisen, Itō Shinsui, Toyohara Chikanobu, Uemura Shōen, Isoda Koryûsai, and Torii Kiyonaga.

The portraits reflected not only changing standards of beauty in Japanese culture but the artist's sensibility. Isoda Koryûsai's prints in the mid-1760's often depicted a willowy feminine figure, whereas around the same time Kitao Shigemasa emphasized the dainty figure. Working in the late 1700s, Utamaro's figures were among the first to become individualized, communicating the figure's personality and mood. Rather than following an idealized treatment, he developed his own style, as his figures were often thin but with proportionally long heads, leading to his work being dubbed ōkubi-e, or "large head" portraits.

Shunga

The term shunga can be translated in Japanese as "pictures of spring," as spring euphemistically refers to sex. The term is also taken from shunkyū-higi-ga, the Japanese term for Chinese scrolls depicting the twelve sexual acts that were an expression of yin and yang. Shunga became a popular subject, as both men and women bought the images, usually sold in small books. Shunga depicted ordinary people, but also courtesans, and while the imagery was predominantly heterosexual, gay and lesbian relationships were also depicted.

The genre was governed by various conventions; figures were usually depicted clothed as this allowed their social standing to be identified, and their genitalia was exaggerated. In Japan the traditional custom of communal bathing meant that the nude was not eroticized. Shunga could be both subtle as seen in the early works of Moronobu, where gestures of the couple or the flowing lines of their sleeves evoke the erotic encounter, or so explicit that, at various times during the Edo period, the government attempted to ban or censor the works as pornographic.

Yakusha-e

Yakusha-e, or "actor pictures," were prints depicting kabuki actors. Often sold in single sheets, the prints were inexpensive and were available as souvenirs following a particular theatrical production. The prints also helped promote the actor's celebrity, and, aware of this, kabuki theatre productions would sometimes invite artists to attend rehearsals. In early yakusha-e, actors were depicted as generic types, though noted masters like Katsukawa Shunshō began to create realistic portraits. However, the greatest master of the genre Tōshūsai Sharaku was not associated with any school, as shown in his dynamic and often unflattering treatments that revolutionized the genre in the late 1700s.

Kachō-ga

Another major genre of ukiyo-e were kachō-ga or "bird and flower" paintings, a style influenced by the Chinese traditional genre of flowers, birds, fish, and insects painting. Blank space was an important element of kachô-ga, reflected in selecting only a single species of bird paired with a single plant, and leaving much of the surrounding space as broad planes of color, in order to create the sense of nature's simplicity and harmony.

As a traditional genre of painting, making bird and flower images created a sense of artistic authenticity for ukiyo-e artists, establishing their work as part of a long tradition. A number of them, including Hokusai and Hiroshige, were to create such works, often including the text of a classical poem or making an allusion to a historical or cultural reference..

Landscape

The shogunate, or military government, of the Edo period required that all feudal lords had to own residences in Tokyo (Edo) and divide their time between residence in the city and their domains. As a result, five major highways were built, like the Tôkaidô Highway, spanning over 300 miles between Tokyo and Kyoto, which became thoroughfares for merchants, pilgrimages, and sightseers who were drawn to famous places. These places had an often spiritually historical significance, influenced by the Shinto religion of Japan, which stated that each place was occupied by kami, which has been variously translated as 'god,' 'spirit,' or 'divine essence.' Shrines in honor of kami were common throughout Japan. Katsushika Hokusai and Utagawa Hiroshige are the most renowned ukiyo-e artists of landscape art. Hiroshige made landscape a primary emphasis as seen in his Fifty-Three Stages of the Tôkaido (1833-1834) and One Hundred Views of Famous Places of Edo (1856-1859). Hakusai's Fifty Views of Mount Fuji (1830-1832) shows a variety of scenes: from farmers in their fields to travelers on a road - while the ever-present holy Mount Fuji, is in the background - traditionally viewed as containing the secret of immortality in Japanese culture, dominates the background.

Later Developments - After Ukiyo-e Japanese Prints

In Europe, the arrival of woodblock prints in the 1850s spawned the loose movement called Japonism (Japonisme in French). This craze for all things Japanese, had a great, almost immeasurable, impact upon artists and artistic movements. James Abbot McNeill Whistler, who led both the Tonalism painting movement and the Aesthetic Movement, was greatly influenced by the Japanese prints's use of color and composition. Most of the leading Impressionists, like Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt, Claude Monet, and Post-Impressionists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin, were inspired by ukiyo-e, as was Gustav Klimt whose work led the to the development of Art Nouveau.

However, the same opening to trade that led to Japonisme in Europe fed the decline of ukiyo-e in Japan. The influx of European ideas, technology, and art radically transformed the culture, and traditional ukiyo-e ended in the 1880s. Though some artists were to continue working in prints, the market for them had disappeared, replaced by the desire for European inspired art.

In early-20th-century Japan, several Japanese art movements were influenced by ukiyo-e. Nihonga, a school that emphasized traditional Japanese painting, as opposed to Western influenced work (called the Yōga movement), was inspired by ukiyo-e artists like Kōno Bairei. Additionally, the sōsaku-hanga and shin-hanga movements were to revive elements of ukiyo-e.

The Sōsaku-hanga, or creative prints, movement was launched in 1904 with the creation of Kanae Yamamoto's Fisherman (1904). The artist eschewed the traditional collaborative process to make the woodblock print, drawing, carving, printing, and publishing it on his own. The movement emphasized this solitary process and connected it to a modern sense of art as an expression of individuality.

In 1915 the Shin-hanga, or new prints, movement followed. In contrast, shin-hanga returned to the four person ukiyo-e process and focused on traditional ukiyo-e subjects while being greatly influenced by Impressionism and creating prints primarily for Western art dealers and collectors. Hashiguchi Goyô's Woman at Her Bath (1915) reflected both the influence of Kitagawa Utamaro and Jean-Auguste-Domique Ingres in its depiction of a nude from Western tradition.

Both the shin-hanga and sōsaku-hanga continued in the following decades, attracting subsequent generations of artists. Both movements underwent a revival following World War II when prints became popular with Americans during the American Occupation of Japan.

In the 1950s, some creative print artists like Hagiwara Hideo turned to abstraction and the next generation, including Keiji Shinohara, began revisiting and re-conceptualizing ukiyo-e. Shinohara moved to the United States in the early 1980s where he has collaborated with such noted artists as Balthus, Chuck Close, and Sean Scully. Ukiyo-e also influenced the flat colors, subjects, and black outlines of Japanese anime and manga. The founder of the Superflat movement, Takashi Murakami, was influenced by the Edo period's eccentric painters, as seen in his Durama paintings (2011). Similarly, in the West, contemporary artists continue to turn to Japanese prints, as seen in the British contemporary artist Julian Opie's saying of Hiroshige's prints, "I often use them as a source of inspiration."

Useful Resources on Ukiyo-e Japanese Prints

-

![Utagawa: Masters of the Japanese Print 1770-1900]() 17k viewsUtagawa: Masters of the Japanese Print 1770-1900Our PickBy Brooklyn Museum

17k viewsUtagawa: Masters of the Japanese Print 1770-1900Our PickBy Brooklyn Museum -

![UKIYO-E]() 39k viewsUKIYO-EBy Begin Japanology

39k viewsUKIYO-EBy Begin Japanology -

![Ukiyo-e woodblock printmaking with Keizaburo Matsuzaki]() 719k viewsUkiyo-e woodblock printmaking with Keizaburo MatsuzakiBy Art Gallery of New South Wales

719k viewsUkiyo-e woodblock printmaking with Keizaburo MatsuzakiBy Art Gallery of New South Wales

-

![How Did Hokusai Create the Great Wave?]() 487k viewsHow Did Hokusai Create the Great Wave?By Christie's

487k viewsHow Did Hokusai Create the Great Wave?By Christie's -

![From Utamaro to Modern Beauty]() 43k viewsFrom Utamaro to Modern BeautyOur PickBy Art Documentaries

43k viewsFrom Utamaro to Modern BeautyOur PickBy Art Documentaries -

![Inventing Utamaro: A Japanese Masterpiece Rediscovered]() 2k viewsInventing Utamaro: A Japanese Masterpiece RediscoveredBy Freer/Sackler

2k viewsInventing Utamaro: A Japanese Masterpiece RediscoveredBy Freer/Sackler -

![Hokusai and Hiroshige: Great Japanese Prints from the James A. Michener Collection]() 93k viewsHokusai and Hiroshige: Great Japanese Prints from the James A. Michener CollectionBy Asian Art Museum

93k viewsHokusai and Hiroshige: Great Japanese Prints from the James A. Michener CollectionBy Asian Art Museum