Summary of Orientalism

Populating their paintings with snake charmers, veiled women, and courtesans, Orientalist artists created and disseminated fantasy portrayals of the exotic 'East' for European viewers. Although earlier examples exist, Orientalism primarily refers to Western (particularly English and French) painting, architecture and decorative arts of the 19th century that utilize scenes, settings, and motifs drawn from a range of countries including Turkey, Egypt, India, China, and Algeria. Although some artists strove for realism, many others subsumed the individual cultures and practices of these countries into a generic vision of the Orient and as historian Edward Said notes in his influential book, Orientalism (1978), "the Orient was almost a European invention...a place of romance, exotic beings, haunting memories and landscapes, remarkable experiments". Falling broadly under Academic Art, the Orientalist movement covered a range of subjects and genres from grand historical and biblical paintings to nudes and domestic interiors.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

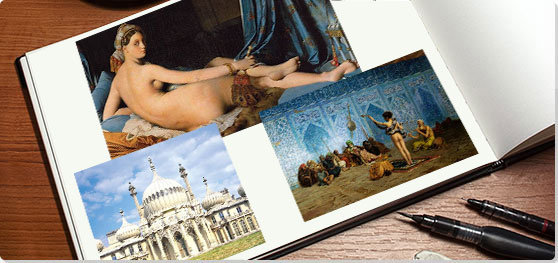

- One of the keys genres of Orientalism was the harem picture. Denied access to actual seraglios, male artists relied on hearsay and imagination to depict opulent interiors and beautiful women, many of whom were Western in appearance. The genre also allowed artists to depict erotic nudes and highly sexual narratives outside of a mythological context as their exotic location distanced the Western viewer sufficiently to make them morally permissible.

- Orientalism disseminated and reinforced a range of stereotypes associated with Eastern cultures most notably regarding a lack of 'civilized' behavior and perceived differences in morality, sexual practices, and character of the inhabitants. This often aligned with propaganda campaigns initiated by Britain and France as colonializing powers and images are best viewed within the context of Europe's political and economic relationships with Eastern countries.

- Many Orientalist images are infused with rich colors, particularly oranges, golds and reds (although blue tiles are also prevalent) as well as decorative details and these operated in conjunction with the use of light and shadow to create a sense of dusty heat that Westerners would associate with the prevailing view of the Orient.

Artworks and Artists of Orientalism

Grande Odalisque

This work shows a reclining nude who turns to look at the viewer and various elements - the peacock feather fan she holds, the colorful turban she wears, a hashish pipe at her feet, the drapery and bedding - situate her within an imagined harem containing a fusion of Turkish and Babylonian iconography. By placing the woman within an Oriental setting, Ingres was able to depict a European nude with frank eroticism, made acceptable by the exotic context. The nude references classical works such as Titian's Venus of Urbino (1534) and Giorgione's Dresden Venus (1510), although the pose is most directly drawn from Portrait of Madame Recamier (1800) by Jacques-Louis David.

The painting, commissioned by Queen Caroline Murat of Naples, is notable for its anatomical distortions, which are meant to draw and titillate the erotic gaze of the viewer. The woman's right arm is longer than her left, and, her exaggerated spinal curvature would be accurate only if she had several extra vertebrae. Ingres employs an exquisite Neoclassical line and high finish to create a sense of objective observation, as if merely conveying what he sees, while, at the same time, his distortions of form for emotional effect bring in a Romantic element. His approach, combining an imagined scene with a polished technique, while exaggerating exotic and erotic elements, was to form the foundation for much of the Orientalist academic painting of the 19th century.

The odalisque became a notable element of subsequent art, as seen in Édouard Manet's Olympia (1863) and the Fauve works of Henri Matisse. At the same time, this image has become a flashpoint for contemporary feminist and post-colonial art, as the Guerilla Girls, a feminist art collective calling itself the "conscience of the art world" repurposed this image in 1989 through the addition of a gorilla mask, to call attention to the art world's inequity, using it to pose the question "Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?". A number of other contemporary artists have also reframed the work, as seen in Renee Cox's Baby Back (2001) critiquing male European views of African women. The Moroccan artist Lalla Essaydi decontextualizes this work in her Femmes du Maroc: Grand Odalisque (2008), stating that through her reimagining she seeks "to present myself through multiple lenses as artist, as Moroccan, as Saudi, as traditionalist, as Liberal, as Muslim. In short, I invite viewers to resist stereotypes".

Oil on canvas - Louvre Museum, Paris

Women of Algiers in their Apartment

Set within an Oriental interior, furnished with Persian rugs and woven tapestries, this painting focuses on four women. One on the left reclines in an odalisque position, her half-shadowed gaze appraising the viewer. To the right two women appear to be in conversation and on the far right a black slave with her back to the viewer turns as if caught in midstride as she leaves the room. The arrangement and poses of the seated women are open and seem to invite the viewer into the private space, this is juxtaposed, however, with the challenging expression of the woman to the left. Although the image does not contain the overt eroticism of the Grande Odalisque, the loose clothing and dishabille appearance of the women alongside the Orientalist tropes such as the inclusion of a narghile pipe point towards their role as courtesans. The painting presents a complex contrast between Delacroix's detailed studies of dress and interior decoration made during his visit to Tangiers in 1832 and his incorporation of these into the European fantasy of the harem.

With this image, Delacroix gave Romantic impetus to the Orientalist genre of harem painting, while employing his scientific approach to complementary and contrasting color. The rich color palette combined with the soft depth of the shadows and the rays of sunlight that fall diagonally into the room from an implied window on the left, creates a sense of warm and vibrant intimacy. As Paul Cézanne said of Delacroix's work, "All this luminous color...It seems to me that it enters the eye like a glass of wine running into your gullet and it makes you drunk straight away."

This painting influenced countless artists as seen in Pierre-Auguste Renoir's Parisiennes in Algeria Costume (1872) and most notably Pablo Picasso's fifteen paintings series, Les Femmes D'Algers (1954-1955). Jonathan Jones has noted that the work "is one of the first 19th-century masterpieces of French eroticism, a radical genre that would lead through Courbet's Origin of the World (1866) and Manet's Olympia (1863) to Picasso's own revolutionary 1907 work Les Demoiselles d'Avignon." The work has also provoked contemporary artistic responses, as seen in the Algerian Houria Niati's No To Torture (1982), a series that as art historians Nicholas Serota and Gavin Jantjes wrote, questions "the exotic stereotype created by Delacroix's women of Algiers and perpetuated in Picasso's fifteen canvases based on the same work. Historically Delacroix's original coincides with the establishment of French colonial rule in Algeria, and Picasso's abstracted versions mark the end of that rule."

Oil on canvas - Louvre Museum, Paris

Scene in the Jewish Quarter of Constantine

This painting depicts two Jewish women and a child who sleeps in a basket suspended by ropes. The room, poorly furnished and simple, with its neutral colors creates a contrast with the vivid color palette of the women's clothing, headscarves, and jewelry. The woman on the right whose gaze rests on the child, conveys a maternal solicitude, while the younger woman on the left, looks forward, as if daydreaming. Chassériau combined the emphasis upon figurative line of his teacher Ingres with the influence of Delacroix's rich colors to create his own unique style, capturing the emotional resonance of his subjects.

Chassériau saw this scene during a trip to Algeria in 1846 and made a preliminary sketch, writing, "I have seen some highly curious things: primitive and overwhelming, touching and singular. At Constantine, which is high up in some enormous mountains, one sees the Arab people and the Jewish people [living] as they were at the beginning of time." In this image he conveys the strangeness of the scene by emphasizing the basket suspended from the ceiling, its ropes creating a triangle that fills the center of the frame, this is juxtaposed with the domesticity of the women, a contrast of the everyday and exotic. The women's dress indicates that they are wealthy but this is at odds with their environment and the woman on the left does not wear shoes, a detail associated by Europeans with the 'uncivilized East'. This aside, the women themselves are complex and individualized, rather than stereotypical. As art historian, Marc Sandoz, wrote the artist "seems to have been seeking a way to revive and modernize contemporary portraiture" by emphasizing the internal psychological realms of his subjects.

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

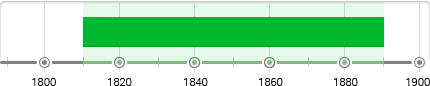

The Royal Pavilion

The Royal Pavilion at Brighton showcases an Oriental style that incorporates a vast assortment of motifs and details from India, the Middle East, and Asia, featuring Indian Mughul-style architecture, Middle-Eastern minarets, and Chinese pagodas. A large onion dome becomes the visual focus of the building, its verticality emphasized by the two tall minarets on either side, and the columns symmetrically arranged beneath it. The pale stone, large windows, fretwork and horseshoe arches create a sense of light and airiness that replicates the feel as well as the appearance of Eastern architecture. The result is a building that is a composite of architectural ideas to create a fantasy palace of lavish extravagance, not unlike the "stately pleasure-dome" discussed in Samuel Taylor Coleridge's Kubla Khan (1816), a classic of Romantic poetry.

The Pavilion was designed and built for George, Prince of Wales (later George IV), who was fascinated by Oriental themes and exotic styles. The architects Henry Holland, then Peter Frederick Robinson were involved in the early stages of building work, but the appearance of the Pavilion today is fundamentally the design of John Nash who began working on the project in 1815. Nash drew inspiration from Oriental Scenery (1795-1808), a six-volume work by Thomas and William Daniell. The architect used an innovative cast iron structure for the building and pioneered the use of wood prestressed beams, and laminated ribs to create the striking shapes. The interior design was completed by Frederick Crace and Robert Jones and was equally fanciful featuring Indian and Chinese design elements. The work is considered a landmark of Orientalist architecture.

Cast iron, wood, brick, stucco, other construction materials - Brighton, UK

Jerusalem, Valley of Jehoshaphat, Tomb of Saint James

This photograph focuses on the Tomb of Saint James in the Valley of Jehoshaphat, its four columned entrance in the center of the image. The Valley, including tombs of other Biblical figures such as Absalom and Zechariah, is believed by Christians to be the place where the Last Judgment will occur. Emphasizing the black tones in the entrance to the tomb, the photographer creates a feeling of solemn mystery in what is beyond the columns. The stone cliff, cracked by shadowy fissures, fills the pictorial frame creating a strong sense of endurance and immovability, echoing the significance of the Valley to Christian belief. Salzmann wrote that his photographs adhered to "biblical text from which I have not erred, and that I have always taken as a base and starting point for my observations".

In 1853 Salzmann first went to Jerusalem to photograph Biblical sites, following the archeologist Félicien Caignart de Saulcy's presentation that argued that various architectural features in Jerusalem dated to the time of the Biblical kings David and Solomon. In the dispute that followed, Salzmann felt that photographs could provide an objective account. After several months in Jerusalem he returned to France, where his images were shown to much acclaim. As a result, the Ministry of Public Instruction gave him a commission to visit the Middle East to photographically study sites important to the Crusades. This photograph was part of the series that he created on this trip and was published in his book Jérusalem. Etude et reproduction photographique des monuments de la Ville Sainte depuis l'époque judaïque jusqu'à nos jours par Auguste Salzmann, chargé par le Ministère de l'instruction publique d'une mission scientifique en Orient (1856).

While serving the purposes of accuracy, Salzmann's photographs also evinced an artistic mastery as art critic Loring Knoblauch writes, "One of the highlights...is Salzmann's repeated use of deep black tonalities, a relative rarity in 19th century processes....[his] studies of enclosures, cloisters, and colonnades use the darkness of the cast shadows as a key compositional feature." In his search for historical and biblical truth, Salzmann was very much an Orientalist, seeing the world of the Holy Land as ageless and frozen in time, while employing the most modern of tools to research it. As Alison Meier writes, "Salzmann represents an outsider's 19th-century attempt to find that...past through its visible details. With their heavy tones, the prints are beautiful, but they're also a visual exhumation of time, using photography as the excavator".

Salted paper print from paper negative - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Finding of the Savior in the Temple

Hunt's painting depicts Jesus as a boy, who faces the viewer and leans toward his mother who speaks into his ear, while Joseph stands attentively behind them. A huddle of Jewish elders and young scholars, to whom the boy had been preaching, begins in the lower left and extends into the dark interior of the temple. The scene is dramatically focused on the contrast between the Holy Family, energetically upright, Europeanized in appearance, and the Orientalized Jewish elders, passively sitting on the floor, many of them hidden in shadow. To the far right, various elements including a dove, the mast of a fishing boat with several fisherman, and a bearded man praying in front of the temple, allude to the Holy Spirit, the twelve disciples, and the Messianic promise. The boy leans towards the future, while looking out at the viewer with a gaze that conveys the religious significance of the moment.

Hunt was one of leaders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and this work shares the movement's interest in painting naturalistic scenes taken from literature, in this case the Biblical story of how Joseph and Mary, looking for Jesus who had wandered off, found him preaching in the temple. Hunt was drawn to the subject because of his own religious conversion in the 1850s, and as F. T. Palgrave, an art critic and friend, wrote, the picture showed "the turning-point from prophecy to fulfillment; the child's first consciousness of who he is, the earliest call to his mission, the revelation of himself to himself."

Hunt wanted the work to be accurate in its ethnographical details and went on a trip to the Middle East to learn of the people and culture, which he represented precisely in this image. As literary historian George P. Landrow writes, "the realistic detail that so many critics took to be the incarnation of a purely scientific attitude functions to aid the spectator in experiencing the scene emotionally." The Orientalism of the scene and the juxtaposition between the detailed rendering of the Jewish listeners and the Westernized appearance of the Holy Family continues to provoke contemporary debate. As art critic Valdislav Davidzon notes, "In its claiming of Jesus as a Christian European child engaged in oppositional dialogue with his aged ancestors, the painter quite clearly establishes what Saïd could never admit: that the specific 19th-century European fascination with the Orient was in some large part the manifestation of a much older cultural anxiety about the debt that Christian Europe owed to the pre-Islamic East."

Oil on canvas - Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham, UK

Pilgrims going to Mecca

A caravan, led by a number of riders on camels, crosses the desert in heat so intense that color seems bleached out and shadow takes on a sharp solidity. The caravan fills up the canvas diagonally from the center left of the distant horizon to the right center where the pilgrims come into sharp focus, as if sweeping up the viewer into the procession. The forward momentum creates a sense of determined effort. The naturalistic detail of each figure conveys a sense of individuality, while, at the same time, the compact density of the group conveys a sense of shared purpose and community. Shown at the 1861 Paris Salon, the painting was awarded the highest prize, as one critic wrote, "it seemed as if every visitor had become part of the caravan."

In 1856, Belly traveled to Egypt to make the studies for this work, saying that he wanted to paint, like Courbet, "the truly beautiful and interesting features of the everyday life of our fellow men." The artist employs a naturalistic style in the details such as the worn knees of the camels and uneven surface of the earth. At the same time, however, the camels are exaggerated in scale, as evidenced by the dwarfed figure of the man dressed in white walking in the lower center, and a wild looking man, shirtless and with a shaved head, leads the caravan. As a result, the artist both emphasizes the exotic elements for his audience and conveys that the scene is a reality precisely observed. The large scale of the canvas reflects the significance of the pilgrimage to Mecca and to reinforce the religious themes, the artist has painted a man walking beside a donkey, ridden by a woman holding an infant, thus creating an allusion to the holy family and the flight into Egypt perhaps with the intent of portraying the oneness of faith.

Oil on canvas - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Bashi-Bazouk

This compelling portrait depicts a black man in profile, his dignified bearing emphasized by his resplendent silk tunic and an intricate and beautifully colored headdress. The effect is visually dramatic and exotic, as the color palette and use of light and shadow draw the viewer's attention to the surfaces of the materials and the tones of the man's skin. Gérôme made this work after one of his many tours of the Middle East in 1868, but as with most of the artist's Orientalist works it was conceived and created in his Paris studio. Here, a model has been outfitted with the clothing and weaponry that Gérôme collected on his trip to depict a Bashi-Bazouk, or 'broken head' soldier, who was part of the irregular forces that fought for plunder with the Turkish army on behalf of the Ottoman Empire. The artist's staging of the portrait reveals how the European audience valued the sumptuous materials and exotic appearance of Eastern culture, as much as the subjects depicted. As a result, the sitter, his 'broken head' symbolizing soldiers who served without the hierarchal discipline of the regular army and were particularly noted for their ferocity, seems untouched by any contact with battle. Rather the image resembles a modern fashion shoot.

Gérôme was known for his cinematic sense of spectacle, making his work both acclaimed and popular within the Neoclassical world of the Academy. An art critic for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1884 wrote, "There is a great deal of character and dramatic power in the picture," but, later, Gérôme's work fell out of favor, criticized by poet Charles Baudelaire as the leader of "the meticulous school" and seen as staid and artificial. Nonetheless he has had a contemporary influence upon the painter Jon Swihart, and his Policce Verso (Thumbs Down) (1872), a depiction of a Roman gladiator in the ring both popularized the gesture and inspired the film Gladiator (2000).

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Prayer in the Mosque

This painting shows the interior of Mosque of Amr ibn al-As, (built in 641-642) in Cairo, as worshippers gather for one of the five daily prayer sessions. The artist has composed the image in thirds, the worshippers occupy the lower third of the canvas, while the middle third is made up by cross beams that create dynamic visual interest by diagonally intersecting with the verticals of the columns. The upper third of the canvas is given to the repeating shapes of the horseshoe arches and a chandelier around which pigeons fly. The division and structured architectural elements create a feeling of balance in the piece. Similarly, the worshippers are divided into three groupings. A cross section of society is presented, from the wealthy man standing on a prayer rug to a solitary holy man, wearing only a loincloth. A diagonal of men praying extends through the center of the canvas into the distance, conveying the spaciousness of the mosque. The emphasis upon the architecture, its shadowy and light filled depths, and its repeating patterns of red and white create a sense of quiet reverence, of the worshippers as part of a greater reality. At the same time, the figures are static, and that, combined with the construction crossbeams, suggest a reality frozen in the past.

In the 1860s Gérôme began painting a series showing Muslim men at prayer in mosques or outdoors, of which this is considered to be one of his masterworks. At the time of his 1868 visit to Egypt, the Mosque of Amr had fallen into ruin and was not rebuilt until 1875, so to assure accuracy of details, he relied on sketchbooks, the works of Orientalist scholars like Edward William Lane, photographs, and other accounts. A fierce critic of Impressionism, Gérôme emphasized in this work the perspective and architectural composition of the Neoclassical tradition. As art critic Glenn Harcourt has written, his "masterful technical skill draws you into his represented worlds in ways that entice, seduce, and finally force you to grapple with them both on their own pictorial and ideological terms".

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Apparition

This image depicts Salome, dressed in revealing and bejeweled Oriental-inspired dress, as she stops in her dance to point toward the head of John the Baptist, his halo emanating light, floating in the center right of the painting. Behind Salome, her mother dressed in richly colorful clothes, and King Herod, dressed in white Oriental robes, gaze without reaction toward the apparition. The young woman playing a lute, and the executioner, his sword at his side, face the viewer but seem unaware of the severed head floating between them. As only Salome reacts to the vision, the scene becomes deliberately ambiguous, and hovers between vision and hallucination. The scene's setting is taken from the Alhambra in Granada, and its aged golden light, combined with his innovative watercolor technique and use of incised lines and highlighting, led to his work being dubbed Byzantine.

This depiction of Salome renders her as a lustful figure, described by Moreau as "a bored and fantastic woman, animal by nature and so disgusted with the complete satisfaction of her desires [that she] gives herself the sad pleasure of seeing her enemy degraded". As an artist he became obsessed with Salome, creating 25 paintings and watercolors and over 200 drawings of her, so that the subject became identified with his opus. This is the most erotic of his images and his Salome embodies the femme fatale of 19th century literature, who was, at once, both seductive and destructive. He also aligns her with the unfettered sexuality associated with Eastern women in many Orientalist portrayals, particularly images of harems.

The Apparition became the best known of his works, influencing the writers Gustave Flaubert, Stephane Mallarme, and Oscar Wilde, and the artist Odilon Redon, and giving impetus to a wide number of artistic and literary depictions of Salome into the early 20th century. Due to Moreau's treatment, Salome became a late 19th century symbol of Orientalism and his work informed fin de siècle art particularly the Symbolist and Decadent Movements.

Watercolor - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

The Snake Charmer

This controversial work, an example of late Orientalism, depicts a naked boy holding a python that coils around him as he stands on a small carpet before an audience of armed men leaning against a tiled wall. To the right of the boy, an older man sits on a cushion as he plays a fipple flute. Painting in his signature Academic style, Gérôme employs tight brushwork and a highly finished surface to create a near photorealistic approach to make an imagined scene seem like an accurate representation.

Gérôme had visited Constantinople in 1875 but created this image in his studio, incorporating some elements from his trip into the work. The work is a composite, using pseudo-Islamic tiles to create the blue background, and the Arabic calligraphy on the walls has a number of errors, just as the men wear costumes and carry weaponry from a number of diverse tribes. The overall composition, however, both invites the viewer to an erotic view of a child and allows for the viewer to make a moralistic judgment of the men watching. This reinforced stereotypes regarding the perceived difference in morality and sexual practices between East and West. Art critic Jonathan Jones described the work as "a sleezy imperialist vision of 'the east,' where voyeurism is titillated and yet the blame for this is shifted on to the slumped audience in the painting."

At the time, Gérôme painted the work, the French and British governments were emphasizing the Westernization of 'the East' to enlighten its suggested primitivism and depravity, and in many ways the work reflects this movement and the propaganda associated with it. At the same time, the artist was a leading opponent of the Impressionist movement, and as Jones, writes, "this is a glitteringly cinematic slice of orientalist fantasy. Gérôme was the kind of painter the Impressionists were rebelling against - a pristine purveyor of high-gloss dreams."

Oil on canvas - Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts

Beginnings of Orientalism

The Venetian School of the Renaissance

From 1463 to 1479 Venice was at war with the Ottoman Empire, ruled by Sultan Mehmet II. Venice was defeated in a number of regions and subsequently forced to pay indemnities to continue trading on the Black Sea. In 1479, the Venetian government sent Gentile Bellini, the official court painter for the Doge of Venice, as a cultural ambassador to work for the Sultan. Bellini returned to Venice in 1481 but he continued to include Oriental motifs in his artwork and this can be seen in St. Mark Preaching in Alexandria (1504-1507).

Other artists, including Veronese, began to incorporate similar ideas in imitation of Bellini and as a result, a number of Venetian artworks survive which depict Middle Eastern subjects. The lasting impact of this can be seen in Veronese's The Wedding Feast at Cana (1563) which depicts Jesus at the center of the table having just changed the water to wine. On his right are Christian guests and disciples in Western clothes and to his left Jewish guests are dressed in an Oriental fashion. This division, identifying Jewish people through Oriental iconography, became a traditional art treatment, lasting into the 19th century as seen in Gustave Doré's engravings in his La Grande Bible de Tours (1866).

Turquerie, the 18th Century

France entered the Franco-Ottoman Alliance in 1536 and the alliance, which lasted until 1798, led to a number of scientific and cultural exchanges. Most notably during the 1700s Turkish items became very fashionable in France and this was reflected in art of the period. The movement, called Turquerie, was led by artists Jean Baptiste Vanmour, Charles-André van Loo, and Jean-Étienne Liotard, and the style became an element of Rococo art, as seen in Liotard's Portrait of Maria Adelaide of France in Turkish-style clothes (1753).

The Invasion of Egypt 1798

Orientalism, as a fully fledged movement, began with Napoleon Bonaparte's conquest of Egypt in 1798 and his occupation of the country until 1801, leading to an influx of Egyptian goods into France. Books, too, played a role. The Baron Dominique-Vivant Denon, who accompanied the Middle Eastern expedition as an archeologist, published his Voyage dans la Basse et la Haute Égypte pendant les campagnes du Général Bonaparte (1802). This was richly illustrated with Egyptian motifs taken from funeral columns, tombs, and temples and these influenced French decorative arts and architecture. The French government's Description de l'Égypte (1809-22) in 24 volumes with illustrations of all aspects of Egyptian life and culture also had a long lasting influence.

Antoine Jean Gros

Antoine Jean Gros was an early pioneer of Neoclassical Orientalism. The official painter for Napoleon, he was commissioned to paint the Emperor's visit to his plague-stricken soldiers in Jaffa, Syria, after his conquest of the city in 1799. Napoleon in the Plague House at Jaffa (1804), was exhibited at the 1804 Paris Salon to coincide with Napoleon's coronation. The work was intended to act as a propaganda tool, arguing for the necessity of French imperialism in Egypt and placing a heroic spin on an ultimately ill-fated campaign. The architectural setting depicted in the painting echoes Jacques-Louis David's Oath of the Horatii (1784), while an Islamic horseshoe arch, the city walls, a mosque, and a Syrian man distributing bread to the sick lend a historical authenticity. Gros's painting exemplified the Neoclassical approach while pointing the way to Orientalism.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres's La Grand Odalisque (1814) was an innovative work in the establishment of Orientalism as a movement and also in its subsequent domination of Academic painting. Commissioned by Queen Caroline Murat of Naples, the painting drew upon traditional images of Venus, but instead of creating an acceptable context for the nude through mythology, Ingres used a Middle Eastern context. In the 1660's the French began using the word 'odalisque' to refer to a concubine in a harem. Taken from the Turkish 'odalik' meaning 'chambermaid' the word in Turkish culture referred to a young female slave, not a concubine but rather a maid, dressed in the same robes worn by male pages. Ingres's title using the word 'odalisque' yoked to the nude, effectively launched Orientalism, and he later returned to the subject, as seen in Odalisque with Slave (1839).

Ingres never visited the Near or Middle East, but like a number of artists, was what was called 'an armchair Orientalist', relying upon the accounts of others, particularly Lady Mary Wortley Montagu's Turkish Letters (1763). Montague, however, emphasized the contrast between her accounts of the country and the romanticized images produced as part of Orientalism. She notably refuted male portrayals of Turkish baths as sexualized scenes by describing them as, "the Women's coffee house, where all news of the Town is told". Nevertheless, Ingres and other artists took her details and settings as the springboard for their own imagined scenes and subjects.

Eugène Delacroix

In 1832 Eugène Delacroix went with a diplomatic group to Morocco and, during the trip created a number of sketches and watercolors. Upon returning to Paris, he subsequently painted Women of Algiers in Their Apartment (1834). When the work was shown at the 1834 Paris Salon, the art critic Gustave Plance wrote, "it was about painting and nothing more, painting that is fresh, vigorous, advanced with spirit, and of an audacity completely venetian". The painting was a ground-breaking model for what would become the widely popular genre of harem scenes and also created a strong interest in Orientalist subjects among Romantic painters.

Orientalism: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Religious Painting

Orientalism had a noticeable effect on religious painting, as artists sought to lend truthfulness to Biblical scenes. This can be seen in the naturalistic local landscapes that are the setting for Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps' Moses Taken from the Nile (1837) and Joseph Sold by His Brethren (1838). British artists such as William Holman Hunt, a leader of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood traveled to Palestine in the 1850s to employ ethnographically accurate details for The Scapegoat (1854-55) and The Finding of the Savior in the Temple (1854-55) and the Russian Peredvizhniki group employed a Realist approach to their religious scenes set in the Holy Land, as seen in Vasily Polenov's Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery (1887) and Ilya Repin's Raising of Jairus's Daughter (1871).

Genre Paintings

Most famous amongst Orientalist genre painters was Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps. He showed seven paintings depicting everyday life in the Middle East at the 1831 Paris Salon including The Turkish Patrol (1831) and these launched his career. His images, depicting Middle Eastern children at play or merchants in their shops, became particularly popular with the middle class and influenced artists including Delacroix. Other notable examples of Orientalist genre work include Jean-Léon Gérôme's The Mandolin Player (1858) and Alphonse-Etienne Dinet's Girls Dancing And Singing (1902). Demand for Orientalist genre scenes began to spread through Europe leading artists such as the British John Frederick Lewis, the Franco-Austrian Rudolf Ernst, the German Gustav Bauernfeind, and the Italian Giulio Rosati to develop their own related style and images.

The harem genre was the most popular of genres, though closely allied with it were scenes of the slave market. Key examples include Giulio Rosati's Inspection of New Arrivals (not dated), Jean-Jules-Antoine Lecomte du Nouy's The White Slave (1888), and Lewis's The Harem - Introduction of an Abyssinian Slave (1850). These works all depicted the female slave as nude and often emphasized the whiteness of her skin. As Edward Said notes, the popularity of the genre drew upon the idea of the Orient as "a place where one could look for sexual experience unobtainable in the West". Men were not allowed into harems, and so artists, including Ingres, drew upon their own fantasies and hearsay accounts in conjunction with European models to create these images. The sense of the male gaze penetrating the forbidden realm of the harem has been interpreted by later art historians like Todd Potterfield as reflecting the Western desire to conquer the land and the realm of 'the other.'

Architecture and Design

Orientalism influenced architecture and design, initially, as Egyptian motifs and designs were incorporated into the French Empire and British Regency styles and Egyptian inspired furniture and interiors became fashionable amongst the upper classes.

Egyptian influenced design also featured in public monuments and in decorative additions to buildings. While the main architectural style of the period remained Neoclassical, connecting the rising French and British empires to the Roman Republic, Egyptian elements including papyrus columns, window frames that narrowed at the top, and the use of motifs such as the lotus blossom, the head of Hathor, and the sun disc were utilized. Eugène de Beauharnais, Napoleon's adopted son and Arch-Chancellor of the French Empire added an Egyptian portico to his private residence in 1807 and in 1815 Peter Frederick Robinson designed The Egyptian Hall (1815) in London. The style spread throughout Europe and to the United States and can be seen in New York City's prison complex, The Houses of Justice (1838) built in the Egyptian Revival style.

In contrast, The Moorish or Oriental Revival style used pointed or horseshoe arches, ornately patterned trim, Turkish minarets, and Islamic tiles to create fantasy Oriental spaces. A noted example is the Royal Pavilion (1815-1822) in Brighton, UK designed by the architect John Nash, which mixes the Islamic architecture of India with elements from the Middle East. Built later, Arab Hall (1866-1895), part of the London home of the artist Frederic Leighton, included over a thousand Islamic tiles from 17th century Damascus, Iznik, and Persia. As art historian Mary Roberts writes, "Arab Hall was conceived as a gesamstkunstwerk, a secular aestheticist fantasy of suspended time in which historic near eastern craft production was synthesized into an harmonious aesthetic present tense".

Photography

Maxine du Camp was an early pioneer of travel photography in the Middle East. In 1849 he traveled with his friend, Gustave Flaubert who would later write the famous French novel Madame Bovary (1857), on a trip to Egypt, North Africa, and the Middle East. Du Camp made hundreds of calotype prints focusing on monumental sites, and published a number of them in Egypte, Nubie, Palestine, Syrie (1852), the first travel photography book. Another noted photographer was Auguste Salzmann who was commissioned by the Ministry of Public Instruction to study and photograph the noted sites of the Holy Land. He published a selection of his images in Jerusalem: A Study and Photographic Reproduction of the Monuments of the Holy City (1856).

In the 1860s photographers such as Francis Firth and Félix Bonfils began making photographic postcards and mementos for Europeans both at home and traveling in the Middle East. Bonfils, a Frenchman, moved to Beiruit where he created images that were meant to convey the Orient's "pristine character and special cachet". Images were often posed and created in the studio, as art historian Michelle L. Woodward wrote, "What makes much of the Bonfils family's work particularly Orientalist was their explicit effort to capture what they imagined was a timeless, unchanging Orient...By selectively and deliberating choosing only particular elements from the surrounding environment...they strove to meet their, and other European's expectations and interests". Local photographers like Pascal Sébah, who established his studio in Istanbul in 1857, also used Orientalist tropes and catered to public demand for Orientalist genre images. Such images also informed the artistic imagination, Jean-Léon Gérôme, for instance, drew upon various photographic works of the Middle East to create his composite paintings. As Nissan N. Perez in his Focus East: Early Photography in the Near East (1839 - 1885), wrote, "Literature, painting, and photography fit the real Orient into the imaginary or mental mold existing in the Westerner's mind. ... These attitudes are mirrored in many of the photographs taken during this time...they became living visual documents to prove an imaginary reality".

Military Paintings

Antoine-Jean Gros led the way in creating dramatic, military works of Orientalism, as shown in his Bataille d'Aboukir (1799), depicting a contemporary battle fought by Napoleon against the Ottoman Empire. Works such as this were popularized through the propaganda campaigns of the Napoleonic government and battle scenes, often depicting heroic French soldiers and actions against Muslim forces, became prevalent. These themes, though reinterpreted within the Romantic Movement, continued into the mid-1800s and they were given impetus by new wars with the Ottoman Empire.

From 1821-1830, Greece fought for independence from the Ottomans, and European artists and intellectuals identified with the Greeks, as seen in Eugène Delacroix's Massacre at Chios (1824). Drawing upon contemporary accounts of the massacre of the Greeks on the island of Chios, the work reflected Romanticism's emphasis upon dramatic suffering and extreme emotional states. In 1830 the French invaded Algeria, and scenes from the protracted war, lasting until 1847, to colonize the country, was also depicted in paintings such as Theodore Chassériau's Battle of Arab Horsemen Around a Standard (1854).

Artists also drew upon classical history, as seen in Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps' Defeat of the Cimbri (1833), a Romantic treatment of the defeat and massacre of the Cimbri tribe by the Romans in 102. Most of these works associated their Oriental subjects and settings with barbaric cruelty and savagery and this is clearly visible in Delcaroix's work, Convulsionists of Tangier (also known as Fanatics of Tangier) (1837-1838) which depicts the Aïssaouas, a Muslim brotherhood as a dangerous crowd of fanatics.

Later Developments - After Orientalism

The Society of French Orientalist Painters was founded in 1893 with the dual intentions of promoting Orientalism and encouraging French artists to travel to Eastern countries. Key figures in the Society were primarily drawn from the Algerian group of painters and included Alphonse-Etienne Dinet, Maurice Bompard, Eugene Giradet, Paul Leroy, and Jean-Léon Gérôme. Art historian Leonce Benedite acted as president of the Society from its formation through to his death in 1925. The Society provided a communal focus for artists through its regular Salons and publications, but it was also seen as providing support for colonial rule in North Africa and the Middle East.

Despite the work of such groups, by the end of the 19th century Orientalism was already in decline. The style of academic art associated with it seemed staid and out of date as new movements, including Tonalism, the Aesthetic style, Impressionism, and Post-Impressionism had developed in the latter half of the 19th century. Many of these movements, however, were influenced by Japonism, which was closely related to Orientalism.

Primitivism, too, was informed by the groundwork of Orientalism, as artists such as Paul Gauguin turned to the subjects and motifs of Tahiti, and later artists like Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse were influenced by African art. Orientalist-inspired images continued to be made into the 20th century by artists including Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Oskar Kokoschka, and Auguste Macke.

Contemporary artists have similarly referenced the Orientalist works of Delacroix, Ingres, and others, though re-interpreted through the lens of Edward Said's criticism, as well as later feminist and post-colonialist critiques. The Algerian Houria Niati's work recasts the images of Delacroix, as art critic Mary Ann Marger wrote, to dispel "the 19th century concept of the exotic nature of then French Algeria" and the Moroccan Lalla Essaydi's work also reframes the works of Delacroix, Ingres, and other Orientalists. The French-Algerian Zineb Sedir creates video installations and photographs preoccupied with colonialist displacement and history, while the Turkish Nil Yalter's video art work portrays the 'disidentified' woman of Orientalism. Şükran Moral 's performance art The Turkish Bath (1997), and Gulsun Karamustafa's Double Action Series for Oriental Fantasies (2000) also critique Orientalism and it stereotypes.

Huma Bhabha uses found materials to create her sculptures, as seen in her work The Orientalist (2007) depicting what the artist described as an "Egyptian seated figure" to convey "the character of these different materials using only their textural attributes. The Orientalist is very much a cyborg, with a masklike face that reminds me of the monstrous portrait of Dorian Gray. And giving it that title seemed to link Oscar Wilde's metaphor to Edward Said's critique of Western hubris."

Useful Resources on Orientalism

-

![The Orientalists]() 7k viewsThe OrientalistsBy Stephen Meyer

7k viewsThe OrientalistsBy Stephen Meyer -

![Edward Said: On Orientalism]() 38k viewsEdward Said: On OrientalismOur Pick1998 Documentary

38k viewsEdward Said: On OrientalismOur Pick1998 Documentary -

![Jean-Léon Gérôme, The Snake Charmer]() 18k viewsJean-Léon Gérôme, The Snake CharmerBy ClarkArtInstitute

18k viewsJean-Léon Gérôme, The Snake CharmerBy ClarkArtInstitute -

![Introduction to the Royal Pavilion]() 56k viewsIntroduction to the Royal PavilionBy Royal Pavilion and Brighton Museums

56k viewsIntroduction to the Royal PavilionBy Royal Pavilion and Brighton Museums

-

![Eugène Delacroix: Dead and Alive: The Rise of Modern Art]() 38k viewsEugène Delacroix: Dead and Alive: The Rise of Modern ArtOur PickLecture by Christopher Riopelle / The National Gallery, London

38k viewsEugène Delacroix: Dead and Alive: The Rise of Modern ArtOur PickLecture by Christopher Riopelle / The National Gallery, London -

![Delacroix and The Rise of Modern Art]() 20k viewsDelacroix and The Rise of Modern ArtReview by Julian Bell

20k viewsDelacroix and The Rise of Modern ArtReview by Julian Bell -

![Jean-Léon Gérôme]() 14k viewsJean-Léon GérômeLecture by Gerald Ackerman

14k viewsJean-Léon GérômeLecture by Gerald Ackerman -

![Lalla Essaydi: Les Femmes du Maroc]() 4k viewsLalla Essaydi: Les Femmes du MarocOur PickRU-tv

4k viewsLalla Essaydi: Les Femmes du MarocOur PickRU-tv -

![New York Times Conferences]() 1k viewsNew York Times Conferenceswith Lalla Essaydi, Touria El Glaoui, and Farah Nayeri

1k viewsNew York Times Conferenceswith Lalla Essaydi, Touria El Glaoui, and Farah Nayeri -

![Public Art Fund Talks: Huma Bhabha]() 5k viewsPublic Art Fund Talks: Huma BhabhaOur PickThe New School

5k viewsPublic Art Fund Talks: Huma BhabhaOur PickThe New School